For a couple of months, Madanm Mèt, Mèt Anténor, and I had been discussing what we might do for Papouch. We felt badly for him. For a series of reasons, he’s suddenly found himself without friends. It’s a little weird. He has none of the typical qualities of a loner. He’s general exuberant, chatty, witty, and social. But though he’s now sixteen, he’s stuck spending most of his time with his wonderful little cousins, Kristo and Breny, who are 11 and 9. It just isn’t good. We had been talking a lot about how much he needs friends his own age and about how we’d like to cheer him up. But we hadn’t done anything.

We thought of sending him to a week of summer camp. Seventh Day Adventists run one that would have enough supervision to satisfy his parents. But it didn’t work out because Mèt Anténor ended up spending a month in the States at just the wrong moment. Madanm Mèt was unwilling to be left at home with her two daughters without a man in the house. Papouch may be young, but he is a young man. There are aspects of running the house that belong to him and his father. So the beginning of the school year came, and we realized that we had let his summer vacation slip away without taking any action.

Then I had an idea. He would have a long weekend October 15-17. If his parents would be willing to let him miss an extra day of school, he and I could easily take a short trip together. I thought about different places where we could fly inexpensively, figuring that he would very much enjoy a first chance to ride in a plane. My godson’s father, Saül, is from Hinche, the largest city in Haiti’s Central Plateau, and that’s where his family lives. If Papouch and I flew to Hinche, we would have an easy place to stay, ready-made friends to show us around, and a great chance at having a good time.

I looked forward to the trip. I’ve been fond of Papouch since I joined his family on my first extended stay in Haiti in 1997. He’s always been a sweet and joyous little guy. He’s not so little any more, and he’s a little bit sad, but I was glad we would have the chance to spend a couple of days together. His family liked the idea. They’ve gotten to know several members of Saül’s family, so they were confident we’d be in good hands.

Papouch liked the idea as well, so I booked us one-way tickets for Friday morning on the six-seat prop plane that makes the twenty-minute flight to Hinche. I figured that we’d take the six-hour ride back in a truck on Monday. He’d miss school on Friday, but be back in class Tuesday morning.

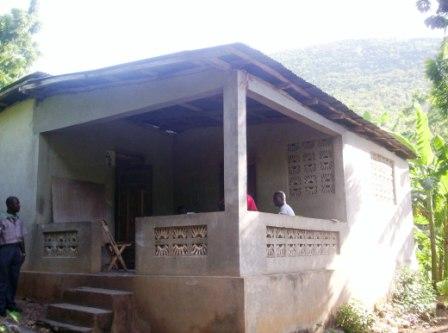

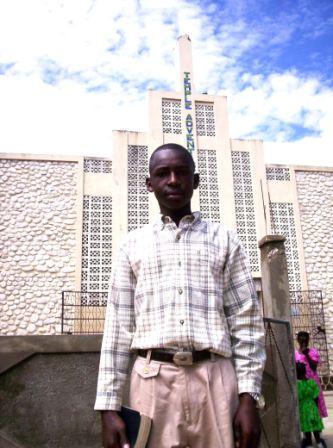

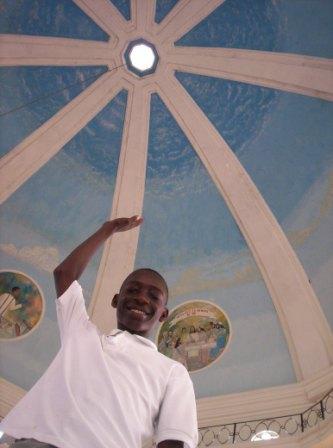

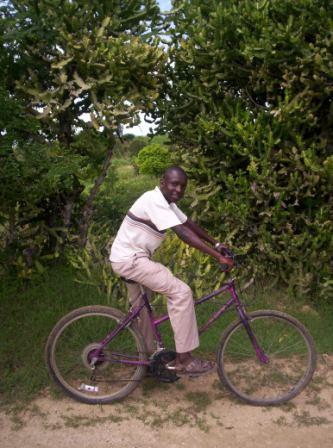

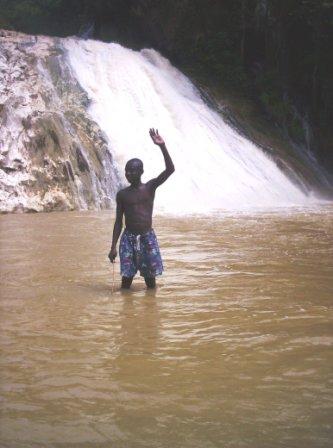

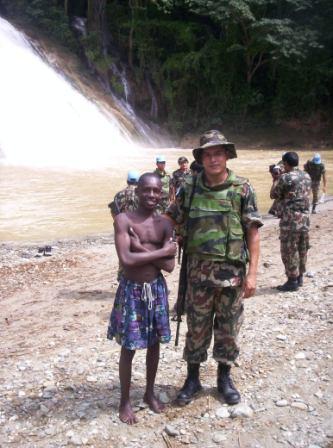

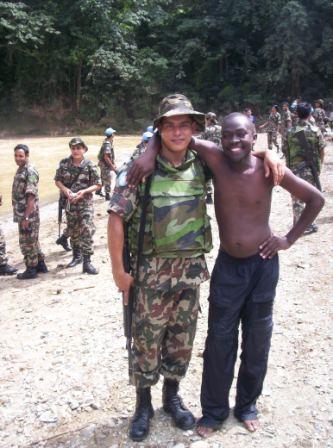

It was a great trip. Saül’s sisters, Nannan and Vivi, were visiting their mother’s house waiting for their schools to open in November, and they took to Papouch and took care of him, feeding him lavishly. Their brothers, Ronal and Felix, spent a good deal of time showing us around. Their mother, Madanm Marinot, was not well, but was pleased that her kids could receive us. Papouch was able to attend church Saturday morning and tour Hinche with Ronal that same day. After Ronal returned from church on Sunday, the four of us rode bikes to Bassin Zim, a waterfall outside of Hinche, where we spent the afternoon swimming.

Papouch liked being in a town where he could get around by bike. He had a great time riding to Bassin Zim and swimming there. He clearly enjoyed the attention that Nannan and Vivi lavished on him, too. They are beautiful young women, and he’s an adolescent boy.

So I was pleased with the time we spent in Hinche together. In retrospect, it seems as though it was a good thing to do.

At the same time, throughout the weekend I was repeatedly struck by how extravagant the gesture really was, how charged it was with a degree of privilege that I, and indeed even Papouch, enjoy here in Haiti.

From its very conception, the trip was marked by privilege. Most of the Haitians I live around do not take trips unless work or family circumstances require them to. They don’t just decide to spend a long weekend having some fun. They are, first of all, too busy. There’s a considerable amount of labor involved in running a Haitian household. That work begins as soon as the work of earning a living pauses for the day or for the week. Secondly, they do not have the extra money that such a trip requires. Though my neighbors are relatively well-off by Haitian standards – Madanm Mèt is fond of remarking that they are, thank God, no worse – they do not spend money on luxuries. Anything they have in excess of their daily expenses needs to be squirreled away, whether it’s for an emergency or just for their children’s next school bill. I was certainly the only one in our area who was going to do something silly like throwing down $30 each for two plane tickets to Hinche just for fun.

But that’s just one way that my sense of privilege presented itself to me over the weekend. I went with Papouch, Madanm Mèt’s son, not with her daughters, Kasann or Valouloun. On one hand, there was a good reason for that: It was, after all, Papouch that we were all worried about. On the other hand, the trip could not help but reinforce the sense of privilege Papouch must feel, and the sense of privilege his sisters must lack, because he is a male and they are females.

All three of Madanm Mèt’s children have chores to do around the house, lots of them. But there is simply no comparison between what’s expected of Papouch and what’s expected of his sisters. And theirs is not the only family that works that way. When Ronal Felix, Papouch, and I left Sunday afternoon to bike to a waterfall for some swimming, Ronal and Felix’s two sisters did not come along. They were at home making food that we would later eat and generally keeping house.

In this context, it might be worth sharing a short anecdote about the beginning of my time in Haiti. When an American friend first spoke to Mèt Anténor about whether he would be willing to host an American, me, who was to spend eight weeks in Haiti, Mèt Anténor immediately said, “Talk to my wife. It’s her house.” He was expressing the very different relationships that he and his wife have with their home. He built the house on his parents land, but once his wife moved in it became hers. She has lead responsibility for everything that goes on in it. Though he pitches in much more than a lot of married men I know – here or elsewhere – housework is neverending for her, and for him it is a matter of a few typically male tasks and a willingness tosometimes help his wife out with the tasks that are hers.

So not only in my running off for a weekend with Papouch, but also in the activities we shared during the weekend, Papouh and I reinforced the privilege we get to feel because we were born as males. For Madanm Mèt and Mèt Anténor, there could have been little question of Kasann and Valouloun going off with us – even if I had felt up to going off with all three kids. They are reluctant to let either slip too far out of their direct supervision.

But even that’s only the beginning of the privilege we experienced. There was another young boy at Madanm Marinot’s house while we were visiting. In fact, he lives there. His name is Jacquelene and he is a restavek. I’ve written of restaveks before. They are children who live in domestic servitude. Their parents turn them over to wealthier relatives or to others because they cannot afford to raise them or because they hope their kids will have greater access to education, to a future, than they can offer.

Jacquelene is Marinot’s godson and he has lived with Madanm Marinot since he was quite young. He rises early and goes to bed late. He works constantly.

I want to be careful: He lives in a house full of people who are fond of him. They call him “Jakito” for short or “the boss” or “ADM”, which stands for “the Administrator”. They joke with him and speak to him gently. He is sent to school. Madanm Marinot and her family are, one and all, good people, and they look at Jacquelene, in a sense, as one of them. Although I’m told that Felix, who lives with his wife and small children next door to his mother, gave Jacquelene a thorough whipping last year, the reason was that Jacquelene’s grades were very low. He was failing. Many Haitian fathers would whip their kids for the very same reason. And I should add that Jacquelene’s grades improved dramatically. He and I spent some time over the weekend doing math together, and he struck me as very bright. He seemed to like the attention, too.

Again, I need to be careful: To say that Jacquelene is a slave – a word that often seems like just the one to describe restavek children – and that the family he lives with are like slaveholders would be worse than inaccurate. It would be terribly unjust. I don’t know what Jacquelene’s home situation was like. Maybe it was worse. I’m told that he doesn’t like to go home, but I didn’t get to talk to him about this.

In any case, when I asked whether Jacquelene might want to go swimming with us Sunday afternoon, I was told that he could not. I suppose he had too much work to do. Not everyone can simply take off and have some fun.

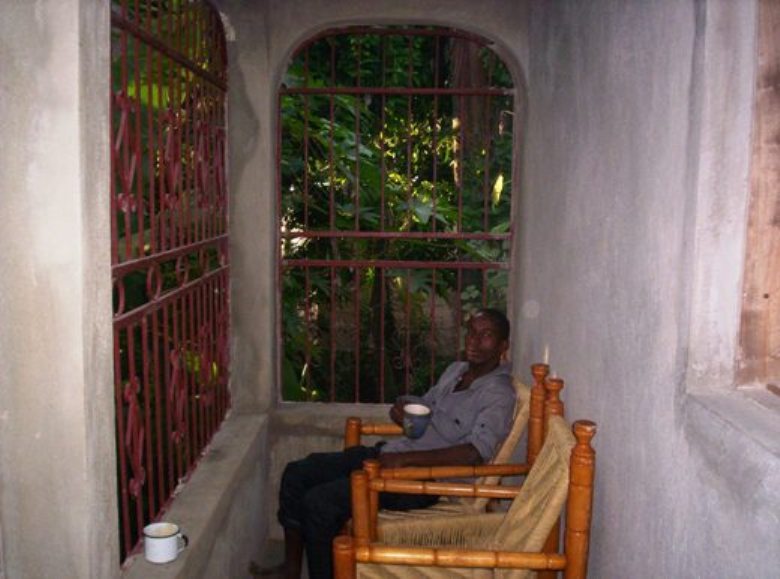

When Papouch, Ronal, Felix, and I got back from our swim, we were beat. We had something to eat, but did very little else before evening. I did some writing and some more math with Jacquelene, but when it came time for bed we were more than ready for it. We set an alarm for 3:45 AM, because the truck back to Pòtoprens was scheduled to pick us up at 4:00.

The truck’s horn sounded outside the front gate just before 3:00, and we were surprised. But we were out the door within five minutes and on our way. It was mid-morning by the time we got to Saül’s house. I wanted to stop to tell him how his mother was doing and to see my makomè and the two kids before heading home. Papouch and I then had a bite to eat in a restaurant in Petyonvil. I told him that he wasn’t hungry when his mother turned him over to me, so I couldn’t return him hungry into her hands. We got on a pick-up truck headed to Malik just as it was starting to rain. The walk home from Malik left us pretty drenched.

I’m glad we took the trip, even though I know that by working within the set of privileges that are customary here, we reinforced them. I’ll have to think of something to do with Kasann and Valouloun.

For some photos of our trip, click PapouchInHinch.