Modeline was excited about her New Year’s holiday. Her baby’s father came back from working in the Dominican Republic. She returned to the abandoned house they had been sharing until she moved back in with her mother’s house while he was away, and got a lot of encouragement from him when he saw her changed situation. “He was really happy. He saw the roofing tin they gave me, and he jumped into the work. He started to prepare the support posts” for their new house. And what’s more, she said that he’s now planning to stay around. “His mother gave him a little bit of land for him to farm.”

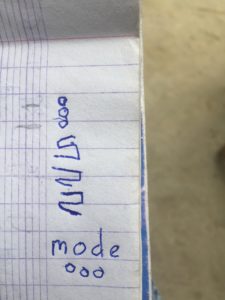

She has made no real progress at writing her name. She works at it seriously but seems dyslexic, though our team doesn’t really have the expertise diagnose her issue. Normally, we just write members’ names clearly for them to copy it in a notebook, and with practice they improve. Some can learn the whole name in one go. Others need to start with a few letters or with only one. But Modeline can’t copy something she looks at. Her case manager, Ricot, will start tracing her name lightly for her with a pencil to see whether she can learn by following the letters her draws for her.

She’s enjoying taking care of her goats and her pig, even though she has to find money to buy the feed that the pig requires. She has only one way to buy the feed right now, and that’s by using money from her weekly stipend. That would be putting pressure on her ability to feed the family, except that she still takes care of younger siblings every day, so her mother still sends her some of the food she prepares.

The relationship with her mother has gotten tense, however. “The case managers tell me to respect my mother, but I yelled at her the other day.”

The issue is her birth certificate. Modeline doesn’t have one, and Modeline blames her mom. Her mother says it was lost in a fire, and Modeline complains that she doesn’t want to help her get a replacement. Modeline’s watched the way the Haitian Ministry of Agriculture has been working to get livestock registered in rural areas, and the ear tags on her own goats, and it only frustrates her. “They say that even animals should have papers, and my mother won’t help me get mine.” What makes it worse is that her daughter will be ready for school next year, but won’t be able to go with a birth certificate and Modeline thinks that she can’t get one for her child without one of her own. Ricot will have to work with her to help her both to get the two birth certificates and to mend fences with her mother.

As I talk with Modeline, I find her cheerful and energetic. But she lacks clarity as well. When I ask her what she would like to do with the money that she’s begun saving, she says that she’d like to buy a mature nanny goat to add to the two that we gave her. It is a good and modest plan. But when I ask her how much she’s saved so far, she has no idea. It is recorded on a sheet that her case manager leaves in her keeping, but she can’t read the sheet and hasn’t kept track of what her case manager tells her. This is a pretty serious issue, because unless she learns to keep careful track of her own things, she’ll have a hard time managing her life.

She has a bigger hope for the future. She wants to move to downtown Lascahobas, where she thinks she’ll find better schools for her little girl. But it is just a hope right now, not yet a plan. She doesn’t know how to do it. “Her father will have to see what he can do,” is all she can suggest.