I was educated in a tradition that sometimes calls itself “liberal”. The word, in this instance, does not refer to the fact that my parents and grandparents were Kennedy and FDR democrats. It refers to my formal education, which was in the liberal arts. I studied some philosophy and some literature, but also some math, some political theory, some experimental science, and even some music. I insist tiresomely on prefacing each piece of my education with “some” to point to the fact that the education was not designed to make me a specialist in any particular area.

In fact, it was designed to make me free. That’s why it’s sometimes referred to as a “liberal” education: because it was designed to liberate me. The motto of St. John’s College, my //alma mater//, is “I make free men from boys by means of books and a balance.” The motto comes from a time before the school admitted women, and sounds better in Latin than in English.

When I ask myself what it was designed to liberate me from, I’m left saying something like “from the shackles of ignorance.” It’s an answer that sounds dated, perhaps, but I think it holds up pretty well to closer examination.

Most of the people I work with in Haiti seem to have more urgent problems than those shackles. Not only that, but the leisure that the sort of education I received – and am very grateful for – requires is almost entirely unknown. The sort of work we undertake here together is very far removed from the seminars I attended all those years ago. But I want to say nonetheless that it’s often liberal in the very same sense that my own education was: It makes those of us engaged in it free.

Here some examples might help.

It’s back-to-school season in Haiti, as it is in the States. The most important difference is, perhaps, that many Haitian children are sitting at home waiting for their families to organize the tuition money they’ll need to send their kids to school, or the money to buy uniforms, or for some other necessity. Some children are already in school, but others will wait until October, November, or even January to get started. About 50% won’t go at all.

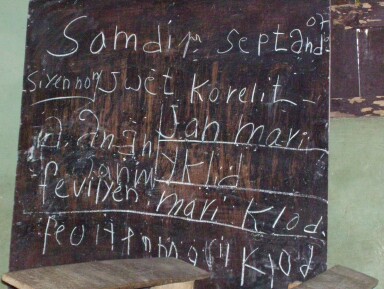

Ti Kèl and Mackenson started last week at the public school in Mariaman, so we got back to work on Sunday. The two of them are my neighbors, now 16. We spend Sunday mornings whenever I’m available doing math together on the blackboard on my front patio. They’re good students, but only in sixth grade. For various reasons, they both started late. We’re a little worried, because there’s a rumor going around that public high schools will no longer accept students over 15 into the seventh grade. They’re pretty confident that they’ll be able to pass the national primary school graduation exam next June, but if they can’t get into the public high school in Pétion-Ville, it may be the end of their education. Neither is in any position to pay for seven years of secondary education at a private school.

We began reviewing some of the stuff we worked on in May and June. Arithmetic with fractions, for example. We worked on all four operations. I thought it would be a good place to start because they were starting to get good with fractions last spring when we stopped. Ti Kèl aced them on his final. I saw his corrected exam. It helped him shock his entire school by coming in fourth in his class, much higher than he ever had. Mackenson, who is generally first in their class, did almost as well. He did better than Ti Kèl on other parts of the final, and so came in first once again.

But I added a twist, and it exposed the fragility of what they knew. I gave them some problems with mixed fractions, and Mackenson in particular was put off. It turned out that he, quite literally, did not know what he was doing. He remembered, for example, that to multiply fractions he need only multiply numerators and then multiply denominators, and that to divide them he need only flip the second of two fractions upside-down and then multiply, but he wasn’t clear enough about what a fraction is to be able to convert mixed fractions into simple ones – like 3 2/7 into 23/7 – much less to add, subtract, multiply, or divide them.

He was frozen, imprisoned, by a certain lack of understanding. He was able to manage well enough when he was on familiar ground, but he lacked the flexibility, the freedom, that real understanding could give him to attack problems that are partly new.

So we spent some time just talking about what fractions are, and he seem to make progress. I’ll know more about how real that progress was in the coming weeks.

I spent part of last week in Pointe des Lataniers. It’s a small fishing village on the very western corner of Lagonav, the large island across a small bay from Port au Prince. I have friends from Lataniers, and we had decided together to organize an experimental literacy center in the town.

As in most parts of Haiti, where official literacy rates are usually given at around 50%, illiteracy is a problem in Lataniers. But, also like other parts of Haiti, Lataniers has various other problems as well: access to safe drinking water, loss of fertile land to erosion and salinization, lack of schools, and more. Our goal was to help organize a literacy center that would also become an engine for community action.

The approach the center would use would be built around REFLECT, a method I’ve written about before. REFLECT is designed to help participants organize knowledge they already possess in a manner that helps them face it, and so make use of it. (See: Learning to REFLECT)

That’s exactly what I saw on Thursday. Participants spent most of class tracing a calendar on the ground as they stood in a circle. The calendar was a listing of each of the ways they make money. For each of their income-generating activities, they went month-by-month, noting when the activity in question would bring in more money, and when it would bring in less.

They made several discoveries, but one that was especially striking. They all agreed that goats bring in much more money in December than in any other month. A very well educated Haitian was with me, and he explained that the demand is higher in December because of the New Year holiday, when lots of people like to eat goat.

But the participants countered that he was missing the real point. Goats are more expensive in December because there are none to be bought. People don’t sell them. And then they explained: They sell goats when they need money. In December, they don’t need money because that’s when they sell their peanut crop. So they don’t sell goats.

As soon as they explained this, they were ready to say that it was silly. They might not need the money right at that moment, but they would be able to make much more money by selling their goats in December anyway. They said they’d do so starting this year.

It’s important to note that every one of them already knew perfectly well before the meeting that they would get more for their goats if they sold them in December. But they had never faced that knowledge in a way that enabled them to make use of it. Talking about the fact with one another, in a conversation about the problems they have earning the money they need to get by, put their own knowledge in front of them. It liberated them from the ways they habitually look at things, and so made them freer than they had been.