I’m worried about Jhony.

Before I go on, I should add that, though my proofreading skills have fallen on hard times, “Jhony” is not an error. That very American name is common in Haiti, but to Haitians the “h” appears to make little sense. They know that it’s there, but they don’t know where to put it. It precedes the “o” as often as it follows it, I think. I don’t suppose it matters.

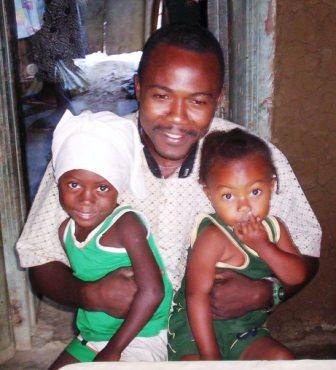

And “Jhony” isn’t even Jhony’s name. His name is actually Makenson. Like many Haitians, the name he really uses is a nickname. Though he says that he’s called Makenson in school, I’ve never heard him addressed that way. In Ka Glo, he’s Jhony Bebette. “Bebette”, his mother’s nickname, is used to identify him when his own nickname is not enough. There are, in fact, other Jhonies and Johnies in the area.

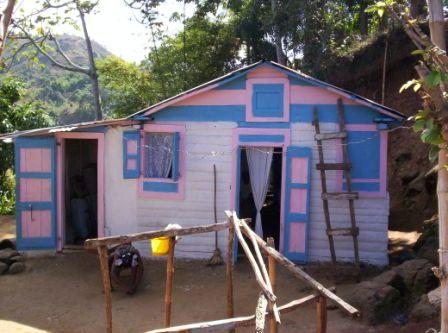

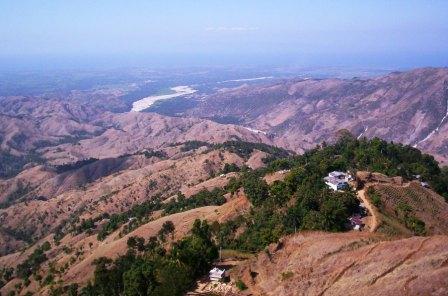

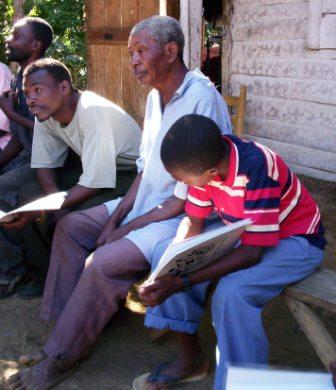

I’ve known Jhony Bebette since I began coming to Ka Glo in 1997. He was seven or eight at the time, but already working hard for his mother in all the spare time he had. She sells bread, homemade coconut candy, and ground coffee from a basket she sets up along the road as it turns uphill towards Mabanbou, the cluster of homes just down the hill from where I live.

She roasts and grinds the coffee herself and makes the candy at home. She buys the bread down the hill in Petyonvil, so she’s got a roundtrip to make on foot each day. That trip, the time it takes to make the other things she sells, and the work around her house take up a fair amount of time, time she can’t spend sitting at her basket, making sales. So her children sit there for her. From a fairly young age, they learn to sell the stuff she offers, to keep track of money, and to make accurate change.

She’s even created a way to do business that works with little children in charge. Everything she sells goes for the same price: a Haitian dollar, which is the usual way to refer to five gourdes. Whenever prices have risen, she’s adjusted the quantities she provides at that price, but she doesn’t adjust the price. That way, making change is, very literally, child’s play.

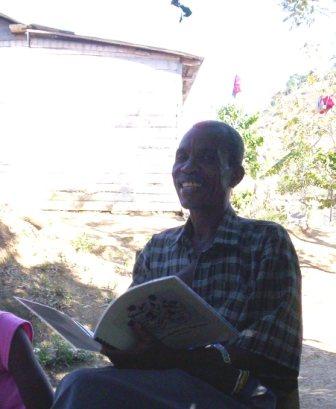

And so I got used to seeing Jhony sitting by the basket, selling his mother’s wares. Or coming to the mapou tree to fetch water. Or, as he grew, walking down the mountain to Malik, where he would meet her as she headed home from Petyonvil, to help her carry her load. He was a cheerful but serious boy and, in his mid-teens, he’s become a serious but cheerful young man.

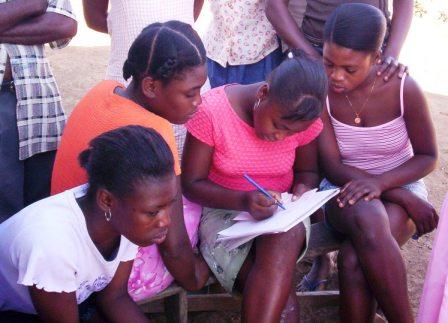

The year before last, he finished sixth grade at Mèt Anténor’s school, the nearby public primary school, and he passed the national primary school graduation exam. He was fortunate enough to secure a place at the public high school in Petyonvil. A good thing, too, because his mother could certainly not afford to send him to a private school. Even a cheap one. The public high school is almost free. He was nervous his first year in secondary school. Things were so different. Different teachers for different courses instead of a single teacher all day long. Much larger classes, filled with kids he didn’t know. But he worked hard, passed comfortably, and started his second year with more hope than fear.

In November, he became ill. I don’t have all the details, but it went something like this: He developed a rash and, at roughly the same time, began experiencing moments of dizzy weakness. The last time he went down to school, in November, he was so dizzy by the end of the day that he had to lie down, and he passed out. By the time he awoke, it was dark. He tried to start the hard uphill hike back home but he couldn’t. He just didn’t have the strength. Fortunately, he saw our neighbor Toto, driving by in his boss’s 4-by-4. Toto put Jhony in the back seat, finished some errands he had to do, and drove him home.

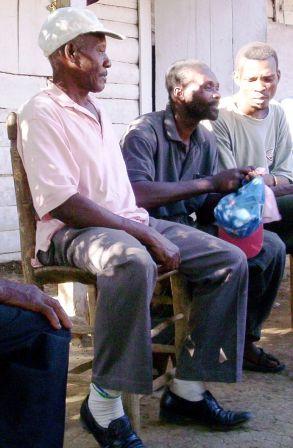

It was a week or so later that I heard about it all. I was away almost all of November, working in the provinces. I immediately asked what the doctor had said, but was sorry to learn that Jhony hadn’t been to a doctor. His mother didn’t have the money to take him, and, even if she did, it’s not certain she would have done so. She and her children belong to a charismatic group of Christians who meet in a home near where her business is, and they had determined that Jhony’s problem was not medical. They believed it to have been caused by the devils who live uphill from them.

These “devils” are the vodoun practitioners who live in Mabanbou. Conservative Protestants tend to be extremely hostile to vodoun, inclined to accuse vodoun practitioners of all sorts of wickedness. Jhony explained to me that he had been told that his soul had been taken to offer as a sacrifice.

Or something like that. I still have a hard time following such stories. I want to be very clear, though: This is nothing more than my very rough rendering of what Jhony told me his church’s leaders explained to him. So instead of taking Jhony to a doctor, they had him move into the church building. There, he could be prayed for constantly and intensively.

And this is where I got involved. At the time Jhony looked awful: thin, downcast, a little lifeless. And the rash was driving him nuts. I spoke to him, and then to his mother, respectfully about the prayer that they were using to heal him, but I also suggested that a doctor might have some good advice. I gave Bebette money to pay for the appointment and for tests and medicines if such were required, and left Ka Glo for another week.

I came back to discover Jhony still living in the church and not going to school. They had indeed been to a doctor, but when the doctor asked for lab tests, Bebette decided to return to the church with Jhony and follow prayer instead. I have no idea how they spent the money, but Bebette is raising five children, so I’m sure there’s no lack of need.

By that point, Jhony was feeling a little better. He had gotten the rash under control with some calamine lotion that I brought him. He was anxious to get back to school because he had already missed out on a lot and the second-quarter exam period was approaching, but he was afraid that he didn’t have the strength to go down to Petyonvil and then return each day on foot. So I gave him the money he would need to take a truck between Petyonvil and Malik, and I left for another few days.

When I returned this time, I was discouraged to learn that Jhony still was not going to school. His mother and their pastor didn’t think he was ready to leave the church. He was starting to look a lot better, but he seemed to be feeling increasingly discouraged. Exams were starting, and he would not be in school for them. If he were to lose a whole set of exams, he would have a hard time passing for the year, and this would have serious consequences.

Generally speaking, it’s not that unusual for a Haitian kid to fail a year of school and to have to repeat it. But slots at the public high school are so desirable that its administration does not let kids repeat grades there. Fail and you’re out. For Jhony, failing school this year could easily mean that his education is over, after a very promising start. And he is very clear about this. As his health and strength have returned to him, his frustration has grown. He thought he was ready to go down the mountain to take his end-of-term exams, but his mother was unable or unwilling to give him either the twenty gouds that roundtrip transportation would cost each day or the fifty gouds to pay the examination fee. With the Haitian goud at about 43 to the dollar, the sums are equivalent to roughly 47 cents and $ 1.16. Though her income is small, and she has a lot of things to manage with it, it doesn’t seem like a lot of money. But this is an extremely difficult claim to judge.

I would have given him the money myself. It wouldn’t be much money for me, either. But I couldn’t convince myself that it would have the effect I was looking for. I have already given his mother money for him. She didn’t use the money I gave her for medical care to pay for medical care, and she didn’t use the money I gave her to pay for his transportation to school and back to get him to school. I do not believe that I should be making decisions for her and her son, but I can’t see myself simply giving them money for I-don’t-know-what either. It’s complicated.

And it gets more complicated in surprising ways. I visit Jhony in the church every chance I get. It’s nice to talk. But if the pastor’s there, he is certain to remind me none too discretely that I said I would buy several sacks of cement towards the construction of the church. This is false. I said no such thing. The truth is that he asked me to buy cement, and I didn’t say “absolutely not”. I said that I would consider the idea. I didn’t want to say “no” outright because so much of Jhony’s immediate future seems to depend on him.

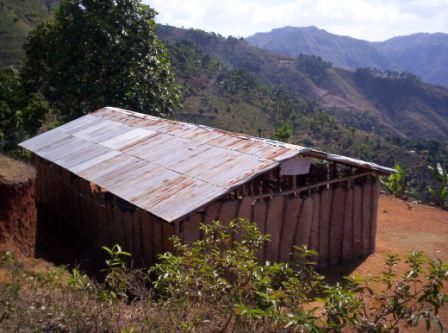

I don’t want to paint Pastor Narcisse in a bad light. He’s taken responsibility for Jhony and for a small church where a growing congregation meets under a woven palm-leave roof that sits on a shaky frame. It would mean a lot to him to get a real structure built, so he would be crazy to let my visits pass without trying to convince me to help him out. At the same time, I’m just not that interested in financing church construction. I have, as they say, other fish to fry.

Soon, enough though, I’ll have to decide whether and what I want to do about Jhony. It seems to me possible, though not certain, that his family is now hoping that I will simply take over his school expenses for them. The interest I’ve shown in him over the course of a couple of years, but especially since he became sick, could very easily have created such a hope. Not deciding anything is not an option, because it would be exactly the same as deciding to leave well enough – or unwell enough – alone.