Spring is supposed to be the season of new beginnings, but for students and teachers – and I’ve been one or the other all my life – things are much more likely to start in September. At least in most of the places I’ve lived and worked. In any case, January 1st has never really felt like the beginning of anything, except the new calendar year.

But this last week has marked the beginning of two of the interesting initiatives I’m involved in here. They have very little in common beyond their starting dates and their adherence to certain core principles. But their very differences argue for writing of them together. They offer a broad view of the very different levels of intervention my work here involves.

The Active Learning Center

Fonkoze’s Active Learning Center is a new branch opening in Lenbe, in northern Haiti, in Mid-January. Normally, opening a new branch, though a challenge full of problems that must be overcome, would hardly be news for Fonkoze. The Lenbe branch will be its 34th, with two or three to be opened closely following it. Fonkoze’s core strategy, but also its style, involves charging hard towards expansion. Its mission is not to change a few businesswomen’s lives, but to change the economy of the nation. And expanding the reach of its services – geographically and otherwise – is a key element of its plan.

But the Active Learning Center is not an ordinary branch. It is designed to be a super-branch. This requires explanation.

The plan to open a branch in Lenbe grew out of a request for a proposal that Fonkoze received. A significant social investor was planning an integrated development project in the Lenbe area, and one element of its plans required microfinance. It asked Fonkoze to take responsibility for that element. So we wrote a proposal, and it was accepted. Finally securing that piece of the financing turned out to be a long process, but Fonkoze succeeded in the end.

Then Fonkoze, along with other microfinance institutions in Haiti, received an invitation from USAID to submit a request for support. USAID’s goal was to encourage innovation in the Haitian microfinance sector. Institutions would be eligible for up to $100,000 to support creative new ways to get things done.

We were excited by the opportunity, but in a very restricted sense. Fonkoze is experimenting with new approaches all the time. Microinsurance, extreme poverty alleviation, social performance management, and new education programs: These are just a few of the innovations Fonkoze is currently managing. In fact, if anything, the amount of innovation going on within Fonkoze all the time is always in danger of exceeding Fonkoze’s management capacity. The “innovation” that Fonkoze needed was not so much a new program for its members and clients, but a new way to study its programs, both old and new, and to make them as strong as they can be.

So, we took advantage of the fact that Lenbe was one of the regions that USAID named as one of its priorities to ask it to invest in the very same branch that our other donor was already funding. The innovation would be the creation of a master branch, or an active learning center. It would differ from an ordinary new branch in two respects: On one hand, it would start with all of Fonkoze’s programs already in place, rather than just the most important core programs; on the other, it would open with a staff selected from Fonkoze’s highest-performing employees, who would live together at the branch, rather than new hires living in homes scattered around town.

The branch would serve Fonkoze in four ways: First, it would be a model branch, a showpiece; second, it would be a place where other employees could come serve short apprenticeships with Fonkoze’s best; third, it would give Fonkoze a place where its very best staff members could experiment with new programs or, more importantly, new approaches to existing ones; finally, it would be a place for field study, where Fonkoze could collect and analyze data that help it better understand both the rural Haitian economy in general, and the finances and lives of its members and clients in particular.

The branch is to be opened later this month, but we decided to start things off with a two-day retreat for its staff. That retreat took place this past weekend.

The retreat had a couple of different objectives. The most obvious was to give the members of the Lenbe staff, who come from all over Haiti, the chance to get to know one another before they begin working together. We also wanted them to accept a detailed set of objectives for the branch and develop a plan for meeting them. Finally, we wanted them to develop the principles with which they will govern the space that they will live and work in.

The weekend’s work included various activities. There were skits. (I played an American missionary, who had to be persuaded not just to change dollars at Fonkoze but also to open a U.S.-dollar account.) There were presentations, like the PowerPoint I gave detailing the history of the Lenbe plan and its overarching goals. There were general discussions, the most important being a detailed look at the financial and social objectives that Fonkoze Director Anne Hastings and I, as grant writers, had presented to funders. And there was small group work, like the time we spent when separate parts of the team – the credit group, the education group, the operations group, and the social performance group – studied the objectives they would most especially be responsible for. They modified the objectives, and developed action plans for attaining the objectives as modified.

In the end, every member of the team, from the branch director to the custodians and security guards, signed a series of four posters we created that had all the objectives written on them. This marked the team’s commitment that they would work together to ensure that every objective would be attained.

The goals are ambitious, far in excess of any expectation we would normally make of a new branch. But the investment we are making in Lenbe is extraordinary, too. The final budget includes funding from four external sources and Fonkoze’s own money as well. It will cost more than three times what Fonkoze usually spends to open a branch, but it will all be worth it if the branch becomes an engine of change within Fonkoze. This doesn’t mean that it will develop lots of new products and services, though we wouldn’t mind if it did. It means, more importantly, that it should discover and test better ways of doing the things we already do and then help us spread that kind of innovation throughout Fonkoze. Fonkoze has 50,000 members and 120,000 savings clients, so even minor institutional improvements can affect very many lives.

The IDEAL Community School in Belekou

This week also marked the opening of the IDEAL Community School in Belekou. I have already shared photos of the first day’s work. (See: TheFirstDay.) But I wanted to write something more substantial about the project.

Since the first time I met with the group in Belekou, one of the needs they expressed was for a school that would offer more kids in the neighborhood the chance for an education. At the time, their idea was that I would simply create a school, much as other foreigners have opened schools in Cité Soleil. They also mentioned a clinic, a library, a water and sewer system, and various other projects.

This was all perfectly sensible on their part. Other foreigners that have been in Cité Soleil have entered with significant resources and predetermined plans. As Haitians say, “mande pa vòlò.” That means, “Asking isn’t stealing.” Belekou is a neighborhood with lots serious problems. Everything they mentioned was a perfectly real need. And they were looking for someone who would address one or more of them.

When I explained that I really only do two things, talk and listen, half of the sixty or so folks in attendance disappeared. A week later, the conversation continued with about thirty, and it’s continued with that same thirty ever since. In the months that followed, they’ve established a bakery and a street-cleaning team.

But the school was their most ambitious project. What started as something as general as a felt need began to take clearer shape when I invited two members of the group to go to Lagonav with me for a visit to the school in Matènwa, a very strong community school, which has been functioning at a high level for years. (See: AnotherExchange.) Other members of the group visited a much newer, less established community school in Fayette.

These two experiences helped the team to begin seeing what a community school could look like. It would be different than anything they had experienced themselves. Non-violent, student-centered teaching and a respectful attitude towards students and parents alike would be the two cornerstones of their approach. In addition, all the little requirements that stand between some kids in their neighborhood and other free schools – uniforms, occasional fees, various other demands that can be hard for parents to meet – would be eliminated.

But even as the guys’ vision cleared, they hesitated. I think they were simply afraid. The two schools they had seen had been opened and were staffed by very experienced educators. They had no reason to imagine that they could do anything similar themselves.

The final push came from a third visit. I took them to see a school near downtown Pétion-Ville, only about an hour’s walk from where I live. It had been opened over two years ago by a community organization that was founded by a group of young people not unlike the guys in Belekou. They too had felt the need to provide education to their neighbors’ kids. (See: www.sodahaiti.org.) Seeing a school that was flourishing in the hands of such young people turned a felt need into a hope with all the shape that the two other visits had given it. What remained was to develop an approach to making their hope real.

Here they might have been stumped, not by perceiving lack of know-how, but by lack of know-how of a very real sort. But the group got lucky. Abner Sauveur, the Haitian director of the Matènwa Community School ( See: www.matenwa.org.) was inspired by their earnestness and their young but clear commitment to ideals he’s been fighting for for much of his life, and decided to do what he could.

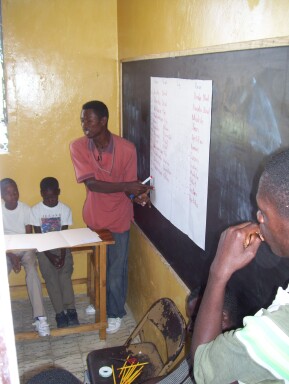

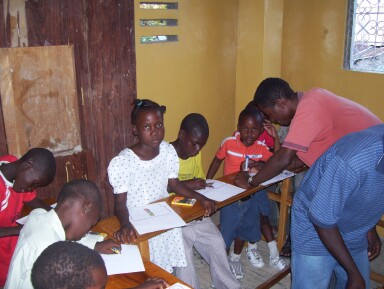

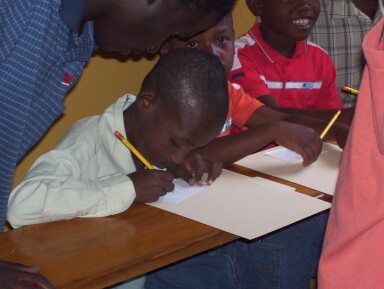

With all his years of experience both as a teacher and as a principal, he was able to do a lot. He took advantage of two visits to Port au Prince to lead long planning meetings for the Belekou guys. Other Matènwa professors got interested. One of them, Benaja Antoine, led a workshop on Creole orthography. Another, Matènwa’s excellent first-grade teacher Robert Cajuste, actually came to accompany the guys through their first week of school.

Meanwhile, IDEAL members who had no interest in teaching, or no confidence that they could become teachers, took responsibility for creating a suitable space or helped in other ways. One team renovated my bedroom. Another made the furniture the school would need.

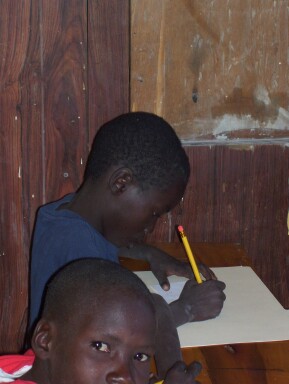

A third team took to the streets, looking for children they could serve. We had a fairly specific profile of the kind of student we wanted. We had no interest, for example, in taking students from already-functioning schools. We wanted none who were already in school and none who were young enough that they might easily wait and start in another school next year. We wanted exactly those kids that existing schools had failed to reach.

The guys found fifteen, and twelve came on the first day. Some are too young, and some have been to school before. As they say, the best laid plans . . .

But the first two days have been wonderful. The kids come more than an hour early, and don’t want to go home. The guys feel their sense of accomplishment, visibly so. Additional parents are already trying to send their kids, and it will be hard to refuse them, as the guys must. But if that is their biggest problem, they’ll be in very good shape.

***

The center in Lenbe and the school in Belekou are fruits of two very different sorts of work. Though I will continue to support the work in Lenbe, visiting whenever I can, consulting with staff, and writing reports, the most important piece of my involvement is over. It consisted mainly of close consultation with Fonkoze’s Director as we developed the idea and wrote the grant proposals that secured the necessary funds.

This might seem like a far cry from my work as a teacher. But the fundamental idea that guides the opening of the Lenbe center is that Fonkoze can improve as a learning institution through the center we are establishing there. And that learning will be participatory and active, just as I believe all learning must be.

Opening the school, on the other hand, has involved close collaboration with the IDEAL team, hours and hours of discussions both with them alone and with people I’ve been able to bring them into contact with. It’s a kind of support that will have to continue, I suspect, for quite some time. Even when they’re doing things very well, they still need to be told that they are. And sometimes they need to be pushed to make the best use of their natural problem solving skills and the wisdom that can come when they listen to one another.

There’s a lot to be said for a job that confronts me with such diverse and different work. It feels like a remarkable, multi-directional extension of the classroom experience that’s long meant so much to me.

Here is a book the children created on their second day of school. It’s about their first day: Firstbook (pdf)