I have several memories of Madanm Marino that will, I think, endure. My strongest impression is of her energy. It was apparent the first time I met her, when she was visiting Pòtoprens with her fourth son. Though a fully-grown young man, he was quite sick, seriously anemic. He had been a promising student, but had been forced to drop out of school. He just didn’t have the strength for it. She was tireless, leading Ronal around, hovering over him, ensuring that he got the attention he needed. He’s fine now.

It was apparent, too, the first time I visited her at her home in Ench. She was a cyclone, working and making an array of other people work to ensure that I, as her guest, had everything I wanted, needed, or could be imagined to want or need.

The memory of that first visit made my visit in October with Papouch especially striking. She was in tears as we said our goodbyes because her failing health had not, in her eyes, permitted her to receive us – this although the son still at home, her two visiting daughters, her son and daughter-in-law next door, another daughter-in-law around the block, and the young boy that lives in her house were all minutely attentive to us, very lavishly hospitable. She was nonetheless unhappy because she herself hadn’t been the one.

But I think that the single image of her that I will always carry with me will be of the last time I saw her. She was in a hospital bed and had known for over a month that she was dying. She was in a lot of pain. The various medications that her family was buying for her when they were able were becoming less and less effective.

It was early evening, just after dark, and a friend and I had come to the medium-sized hospital ward she was in for a last visit before we would head back from Ench to Pòtoprens. As we stood, awkwardly trying to make some kind of conversation, a group of well-dressed women filed into the ward. Most of them were in their 50s, I suppose. They were members of a church choir that she had been part of. The group began to sing slow, soft gospel music, and Madanm Marino, who had been lying down, wanted to sit.

But she didn’t have the strength to hold herself up, so she called her daughter-in-law, Anna, over, and asked her to sit on her bed. Anna very gently raised Madanm Marino and sat directly behind her so Madanm Marino could lean on her. Madanm Marino closed her eyes as she listened to her group’s song, her full weight propped up by Anna’s side. The combination of the grace she exhibited as she faced death and of Anna’s devoted service as her support will be with me always.

That was in January. Madanm Marino passed away on March 3rd. Ronal, the son she had fought so hard to save, was the one who found her in her room, where she had returned from the hospital to spend her last weeks.

The funeral was on the 6th. I didn’t hear about her death until the 4th, so it was something of a rush to get to Ench for it, but I couldn’t be happier that I decided to go. I went with a group of Saül’s Pòtoprens friends. Saül is Madanm Marino’s oldest son, the father of my first Haitian godchild. He’s the live-in custodian in the office of an NGO. Two other of the NGO’s Haitian employees were part of the group: Eklann, who is the housekeeper, and Joseph, who runs errands. Daniel, the custodian for a wealthy doctor who lives next door to the NGO’s office, went with us as well. We slept at the NGO’s office on Saturday night so we could get an early start Sunday morning. We would be going to Ench on the 5th, attending the funeral on the morning of the 6th, and trying to return to Pòtoprens that same day. Ench is a hard five-ten hour journey from Pòtoprens, but I’ve written enough recently about traveling in Haiti, so I’ll leave out those details.

When we arrived in Ench, we were led directly to Rosemond’s house. Rosemond is Saül’s cousin, but he’s also much more. He is Marino’s – that’s Saül’s father – godson, he’s Saul’s godfather, and Saül is godfather to one of his son’s. The two families have thus made a series of decisions over the years that weave them together as closely as could be.

Rosemond is a successful gasoline merchant. Ench doesn’t have a functioning gas station, so gas is sold in gallon jugs by merchants that bring barrels full of it in trucks from Pòtoprens. He has a large house, just around the corner from Madanm Marino’s, and for the days around the funeral, that house became a simple extension of Madanm Marino’s home. It’s where her children put the four of us that came together from Pòtoprens up, and its where not only we four but also where all her immediate family and an array of other guests took their meals.

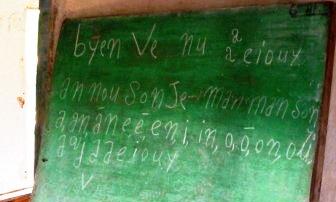

The night before the funeral, there was a wake. It began with a service at Madanm Marino’s church, a memorial of sorts. It involved lots of singing, both by a choir and by those in attendance, a fair amount on prayer, and a sermon. It wasn’t much more than two hours long – a short service by Haitian standards – and it was well-attended. After the service, everyone went back to Madanm Marino’s home, where her husband and children and daughters-in-law and a few other near relations received them as best as they could. They put out chairs, and offered drinks and snacks.

I went around the corner to Rosemond’s house at about 10:00. I was ready for bed. Madanm Marino’s fifth son, a medical student named Job, snuck away with me. He just couldn’t manage any longer. Sleeping space was limited, so the two of us squeezed into the same small bed. I don’t know where the bed’s usual occupant slept.

Job wanted to talk. There was so much on his mind. But he was also exhausted, and knew he had a hard day ahead of him. So he drifted off to sleep soon enough.

The funeral would start with a viewing of the corpse in the church at 7:00 on Monday morning. The service itself would begin at 8:00. So we had to get up and get ourselves ready rather quickly. I felt fortunate that things were starting early, however, because the trip back to Pòtoprens would be long, and I am not accustomed to arriving late.

I wish I had words that could really do the funeral justice. A couple of things seem especially worth mentioning:

First, the yelling. Haitian funerals include a way of displaying grief that is very far from my experience. Mourners, especially women, scream about their loss. They shake. They go into convulsions. They can fall to the floor if unsupported. They shout to the one whom they’ve lost. They shout to other loved ones. They shout to god. They cry. I’ve read about such grieving, but only in Haiti have I seen it. And the sight of it and the sound of it grab every bit of one’s attention.

Second, the ceremony’s length. In my experience, very little of what Haitian’s do in church is brief. Madanm Marino’s funeral was almost four hours long. There was every very long sermon. There were several long, seemingly free-form prayers. But what really made the service long was the third thing I want to mention.

The choirs. By all accounts, Madanm Marino was an enthusiastic member of several churches in her lifetime, from the time she was growing up and then first raising her children in the countryside, to when she moved into the city so her kids could go to secondary school, she was always an active member. She especially loved to be part of her churches’ choirs, and several different churches sent a choir or two to perform in her honor. I think there were seven. Each sang two or three long pieces, and they added up.

The most stunning performances were by her last church’s choir. It was a large group, with maybe 50 members. Not only did they sing beautifully, wonderful pieces in four-six voices. It turned out that their conductor and musical director is her younger brother. He and his wife live next door to her house in Ench, so the brother and sister must have spent very nearly all of his 50-odd years together. She herself was 58 when she died.

His performances were beautiful. He held the choir’s attention without drawing excessive attention to himself. He had been spending much of the funeral walking on and off the stage. Between the choir’s numbers he would walk down to be with his nieces, Madanm Marino’s two daughters, comforting them as best he could. He took a break to give the most unassuming eulogy I have ever heard. It consisted mostly of a short biography of his sister and then a long list of the many loved ones she left behind. At the end of the eulogy he too was overcome but that didn’t keep him from returning a few minutes later to conduct another piece.

We walked from the church to the cemetery, where what had been Madanm Marino was placed in a tomb. From there, Joseph, Daniel, and I ran to get out of our suits and into traveling clothes. We needed to be off. Madanm Rosemond wouldn’t let us go before we had a bite, but we boarded a truck and were on our way to Pòtoprens by 2:00. I was home by 9:00 that night.

Saül contacted me through Job mid-week to ask whether I could return the following weekend to travel back to Pòtoprens wife his wife and their boys. They needed to get back to school – they’d already missed a week – and traveling with both of them was a lot for even Jidit to manage. It was, as always, a long hard ride back from Ench. We left on Monday at about 3:00 AM. The hardest thing for me was not making the trip with Cedrick on my lap. What was hardest was the realization that while I winced and grunted with each painful bump in the road, Cedrick was having a grand time. He seemed to take it as something like a carnival ride.

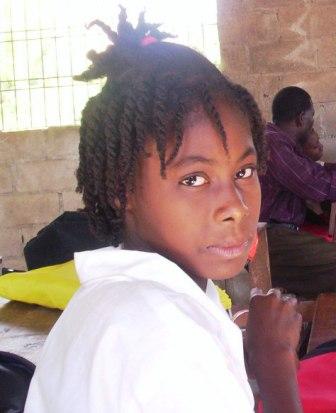

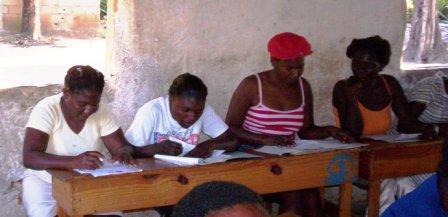

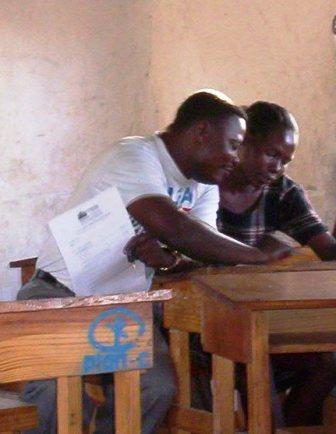

Here are Madanm Marino’s six grandchildren. The second from the right is my godson, Givens. The second from the left is his brother, Cedrick. I took the photo during my second visit to Ench after her death, when I was there to bring my makomé and her two boys back to Pòtoprens.