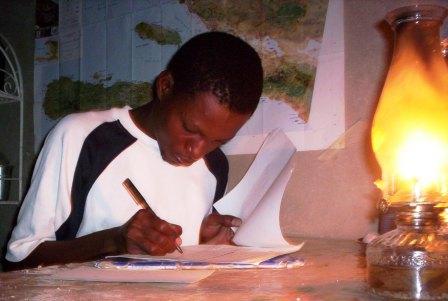

We sat in the meeting room at the top of the school in Matenwa with ten little stones, a pen, and a pile of scrap paper. I was trying to determine whether he knew his numbers, one-four.

He could write them on paper. “2” gave him some problems, but he was even able to write a perfectly good “6” at one point. It soon became apparent, however, that the fact that he could write the various digits did not mean that he knew what they meant. He did not seem to connect a “1” with one thing or a “2” with two things or a “3” with three.

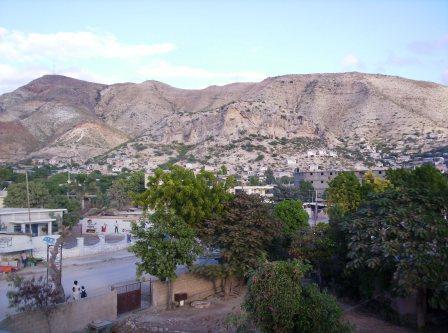

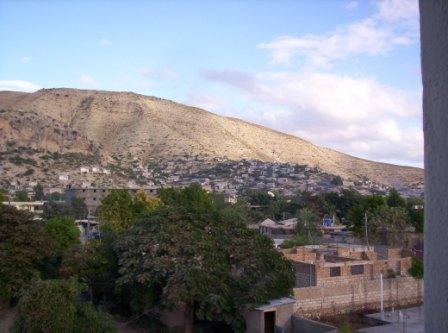

Jantoutou joined Vana’s third-grade class this year. He’d been friends for years with other kids in the class, but hadn’t been going to school. He is what Haitians call a “bèbè”, a deaf-mute, and such children generally miss out on the chance to go to school. There’s just no place for them in a traditional Haitian classroom, where the emphasis is on recitation of memorized texts. There is, for example, a deaf-mute who lives in Nankonble, just a little way down along the hill from where I live in Ka Glo. He’s a full-grown young man, big and muscular, and he makes a living working for the masons and carpenters who build houses in the area. He does the heavy work: mixing and carrying mortar, lugging rocks or cinder block or planks, digging holes. But he didn’t get to go to school. His ability to communicate is limited.

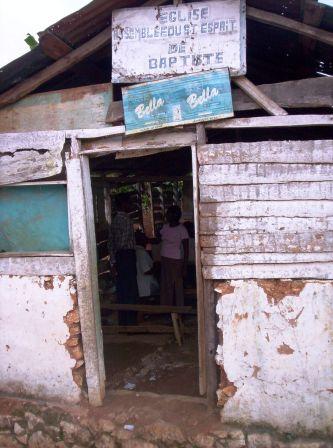

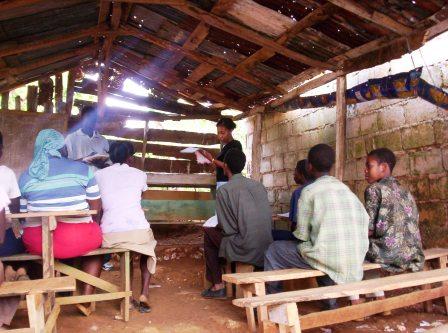

But the Matenwa Community Learning Center is different from almost all other Haitian schools. Teachers there focus on creating classrooms where children can work together to discover the world. The children work individually, in small groups, and in large groups to teach one another and themselves to read, to write, to appreciate and improve the environment that surrounds them, and to learn math and the other skills and information they’ll need as they grow.

And the freer, more participative approach the school takes leaves plenty of room for students who would not traditionally find their ways into Haitian primary schools. I’ve written before of the adult women who attend classes with the Matenwa kids. These women are only the most obvious example of students who would not be in primary school were they elsewhere in Haiti.

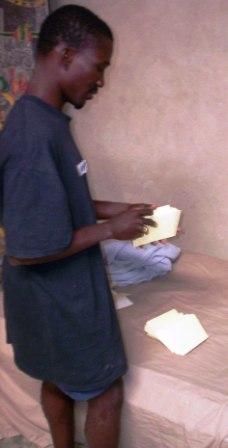

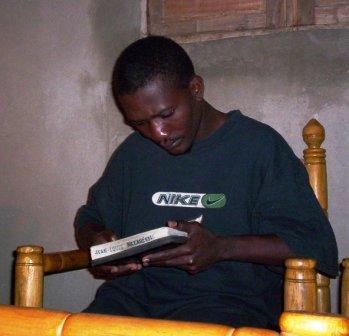

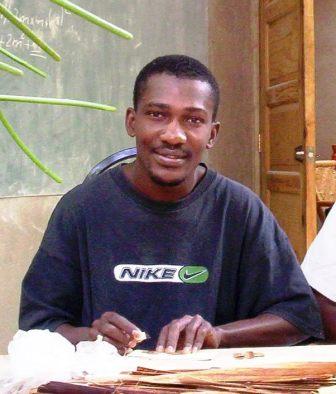

Jantoutou is an example of a very different kind. Vana is happy with his presence in her class. He is growing socially, integrating himself increasingly into the class’s activities. As long as he has something to do, he is hard to distinguish from the other kids. Only when he feels lost does he tend to misbehave. Naturally enough, I suppose. When the kids are writing or drawing, he works closely with another student, copying whatever she does. And so he is getting better at drawing, and he can write some words.

But Vana has been increasingly concerned at the difficulty of determining exactly how much Jantoutou is learning beyond how to behave in a group. It’s hard to be certain what the drawings he creates or the words he copies mean to him. The example Vana cited when I spoke to her was straightforward: He seemed to understand addition problems some of the time, but not always. She knew that he probably needed more individual attention, but with twenty-something other students to worry about, and without experience or training to help her know how to work with a deaf child, she was a little bit stumped.

I certainly don’t know any more about working with deaf children than Vana does. If anything, I know less. She is, at least, an experienced and successful teacher of kids. But I’d become fascinated during my monthly visits to the school as I got to see Jantoutou working in her class, and I was curious to see what doing some math with him would be like. So I asked her whether I could work with him for a few minutes, and she quickly agreed.

I started by making three piles of stones: one with a single stone, one with two, and one with three, and I wrote the appropriate digits under each. I used pointing in an effort to associate the digits with the piles. We then spent about twenty minutes alternating between two games. In one, I would put out one, two, or three stones, and he would have to write the correct digit. In the other, I would point to a “1”, a “2”, or a “3” on a sheet of paper in front of him, and he would have to choose the right number of rocks.

It soon became clear that he had not really been associating the digits with the quantities. He seemed to be choosing digits more-or-less at random. That is, in fact, why I know he can write a perfectly good “6.” He wrote at least two of them that I can remember, though he never had six rocks in front of him at once.

Slowly, his answers became more and more regular, more and more correct. It will take a lot more practice for me to be able to be certain that he’s getting it. I just don’t know what I’m doing. If nothing else he seemed to be having a great time.

I hope to make sitting with him a part of my daily schedule when I’m in Matenwa. Abner Sauveur, the school’s principal, spoke to me about the activity later that day, and he plans to start spending time with him as well.

My work here in Haiti is an apprenticeship. I think of myself as learning all the time. Working with Jantoutou will be a new challenge. I don’t know what he’ll get out of it, but I am very sure I’ll learn a lot.