Yoyo Piman is dead. He was shot on Tuesday by UN forces attempting to arrest him. The guys I know in Belekou shared the news on Thursday.

When I got up to Kaglo Saturday afternoon, I heard the same news from Breny, Mèt Anténor’s eleven-year-old nephew. Yoyo Piman was well known in Haiti. Though perhaps “notorious” would be a better word. He was the second-in-command of the gang that ruled Belekou until the UN overran all of Cité Soleil in February of this year.

He went into hiding, but didn’t go far. He stayed in Belekou, in a small, one-room shack in the midst of one of the neighborhood’s many narrow, unpaved corridors. On Tuesday, someone told the UN forces where they would find him, and they moved in Tuesday night. He tried to flee, and was shot. The guys I know were especially struck by how he died: running barefoot, half-naked, in the middle of the night, through the putrid Cité Soleil mud after four months of hiding in the cramped darkness. A miserable way to end.

I want to be very careful how I write about Yoyo. The most certain fact is that he died accused, but not convicted. When Breny spoke to me about it, he expressed excitement at the death of a terrible criminal. He also enjoyed making fun of Yoyo’s name, which was really a nickname. “Piman” means “pepper”. I don’t know how he came to be called Yoyo Piman. His real name was Junior.

But Breny is a child, and one who lives far away from the reality of Cité Soleil. The guys from Belekou lived their whole lives around Yoyo Piman, and never spoke or speak of him in anything but positive terms. He was someone they knew they could count on: for advice, protection, and a few dollars now and then when they were in need. I’m told that during December he would walk the streets in his neighborhood loaded down with cash. No one in the area would go without a gift to celebrate the coming New Year.

I met him in December, I think. I don’t remember exactly when. I had just rented my room in his neighborhood, and he came for a visit. We had a long and interesting chat. Before even I had begun working in Cité Soleil, the young men who wanted me to come had spoken with Yoyo and Amaral, the real boss. They asked the two to give their blessing to my visits. The guys wanted to do what they could to ensure I could come and go safely. Amaral said I was welcome. But when the collaboration with the guys started to deepen, we wanted to talk with them directly to make sure they were really on board.

The guys chose to ask Yoyo to come by to speak with me. They were never comfortable with Amaral. They neither said nor say anything bad about him. They never really speak of him at all. As much as I can tell, it’s partly in the old “If you can’t say something nice . . .” sense. Except that there’s a difference: Amaral wielded enormous power in the neighborhood. It might have been dangerous to speak ill of him.

So one day, Yoyo came by, and we talked for almost an hour: about the English class Héguel and I were teaching, about the progress of the group, about my impressions of Cité Soleil. He was glad I was working with young people he grew up with. At the time, some of his men were attending the class, and he was glad of that too, though as the battle began to heat up in January, they gradually dropped out. He seemed to feel a leader’s responsibility for them. He assured me I’d have no trouble with him or his people. He had discussed the matter with Amaral, and could speak for them both.

He also spoke of the struggle that he and his gang were embroiled in. Amaral and he felt trapped in an armed struggle with the UN. Amaral’s brother-in-law, Evans, who was the head of the gang in Boston, the neighborhood bordering Belekou on its northern edge, believed, Yoyo said, “in a military solution.” The Belekou did not feel as though it was in a position to separate itself off from the other gangs in Cité Soleil. When the UN finally moved in with all the force at its disposal, blood flowed in Boston, where Evans insisted that his people fight it out. Amaral and Yoyo, on the other hand, had their people lay down their arms. It’s not known how many died in Boston, but in Belekou the UN moved in without opposition and, therefore, without violence.

And Yoyo talked about his life. He had been wanted by the police for several years, so though he could circulate freely within Cité Soleil – the Haitian police still do not enter the neighborhood – he was unable to leave.

Except once. One evening after dark, a longing to see Champs de Mars, the renovated public park in the middle of Port au Prince, overcame him. He hopped on his little motor scooter and gave himself a downtown tour. He said he enjoyed the outing, but could not feel safe outside of his home turf, so he never repeated the experiment.

I try not to kid myself about him. The money he freely gave to neighbors – to all who asked for it and to some who didn’t – did not grow on a tree and it didn’t fall from the skies. I don’t know what business he was in; I doubt he was selling popsicles. But I have to say I liked him and was grateful for his openness to letting me work with the guys. My neighbors in Belekou, who knew him all much better than I, evidently liked him too.

His death provides an obvious moment for looking at how things stand in the Cité. After several months of what can only be called warfare between the gangs and the UN, with guns going off almost constantly, the neighborhood has now been quiet since February. There is a new sense of security, even if it’s rooted in the presence of the tanks that pass by my gate almost hourly throughout the day and night. The tanks and the heavily armed men they carry.

But I recently read a journalist’s interview with a man who lives in the area. The man said that he was pleased with the new security situation. “But,” he added, “You can’t eat security.” Security is not enough. Without the economic opportunities that allow someone to eat and to feed their family, the peace that tanks currently enforce can’t last.

I think that the man’s view of Cité Soleil can be generalized to apply to all of Haiti. A lot of progress is being made these days. There’s a lot of complaining, too. There’s so much work to be done, that the accomplishments to date can be hard to notice. But the local currency is stable, after years of losing value against the dollar. It’s even gained some of its old value. Some roads have been built or repaired. The capital is cleaner because of squads that have been hired to sweep and clear the streets of trash.

And finally there’s the security situation. Streets in Port au Prince that were utterly empty after dark just a year or so ago are now bustling well into the evening: with pedestrians, cars, and street vendors. Adding a couple of hours of street life every day in a country where the vast majority of all economic activity is in the informal sector has to help.

But the progress seems fragile. Prices are starting to rise again as the price of gas goes up all over the world. And there’s still very little work here. As long as the economy fails to provide opportunities for most Haitians to earn their livelihoods, as long as most Haitians live in poverty, political instability is only the next disaster away.

And economic development will not be easy. To paraphrase something Fonkoze’s leadership likes to say in another context: You can’t simply furnish someone with resources and expect them to move forward. You have to accompany them. People need to learn how to plan, how to organize themselves, how to keep track of their own work. Creating economic activity in Haiti will take money, but also lots of labor-intensive, attention-intensive effort.

The complexity of the challenge is before me all the time. I recently watched as a major non-for-profit took the first steps in their plan to create a business for 20 residents of Belekou. Before they had even selected participants, their coordinator in the field had run off with money he collected by charging hundreds of people a substantial fee for submitting their résumés. As far as I can tell, the plan has been postponed. Meanwhile, a woman I know was unable to send her boy to take the national sixth-grade graduation exam because she didn’t have the money to pay the owner of the boy’s school what she owes him. She owes less than half of what she paid the not-for-profit’s coordinator.

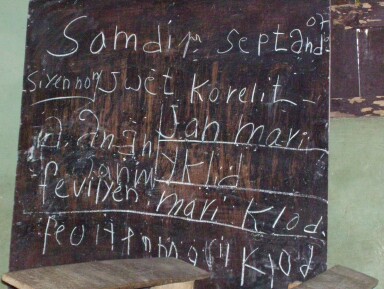

My own work with the guys in Belekou has been increasingly focused on our attempt to establish an income-generating activity. A first plan, to build and sell cheap solar chargers for telephones, seems to have run aground. The guys’ new plan is to open a very small bakery. It seems like a good idea. We’ve found someone willing to lend them the capital they need to get started. The local demand is evident. The very-small scale that they want to start with should be manageable.

“Should be” and “seems like” are not, however, the same as done. It will be a challenge for the guys to organize themselves, to share both the work and the rewards in ways that seem equitable to all. It will be hard for them to keep the earnings in the business, working for them, in a world that’s full of things they want to buy. They are hungry, both for consumer goods and, some of them at least sometimes, for food. Surely there are other challenges that I don’t foresee. And if violence returns, it could easily swallow up whatever progress they have made.

But we have to be optimistic, even if even we can tend to fear what lies ahead. There’s simply no other option. Some of the guys have parents that support them, but not all of them do. And even those who have parents are unlikely to get all the help that a young person needs. Many of them had to drop of school before finishing primary school. A few got somewhat farther, and a few still attend. None have any reasonable prospects of getting a good job. Self-employment is probably their only reasonable hope. For people as poor as they are, there is no real alternative to success.