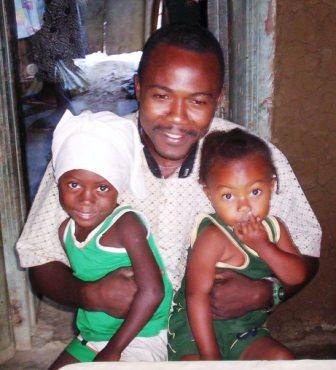

Saül and I have known each other since my activities in Haiti first began in 1997. He’s my //monkonpè//, which is to say that his son is my godchild. So our relation is very much like family. I’ve mentioned him often in my writing, and that reflects his very large presence in my life. In addition to my friendship with him, his wife Jidit, and their children – I rarely enter Pòtoprens without seeing them first or leave it without seeing them last – I’m also close to various other members of his family. His younger brother Job especially, but his other siblings as well.

For the last month, Jidit and the boys have been in the countryside, visiting her family, so Saül has been staying alone in the small, one-room, concrete house where he lives as the custodian of the office of a Christian NGO. While his family is away, I’ve been spending more time there. I’ve even slept there a couple of times. I joke that I’m there to keep an eye on him for Jidit.

Saül’s job as a custodian doesn’t pay much. Though he and his family have free housing, electricity, and water, and though this is no small matter in the Pòtoprens area, the salary is nonetheless low. With two boys in school, things are tight.

But it’s harder than that. He’s the oldest of his parents’ seven children, and the last three are still in school. They depend heavily on him and on Felix, the third of the five brothers, to put them through school and keep them fed, clothed, and housed. This involves a lot of expense. And this past year has been especially difficult, emotionally and financially. His mother’s long illness was very expensive, and her funeral was as well. It’s a little hard to imagine how he could make it on his salary alone.

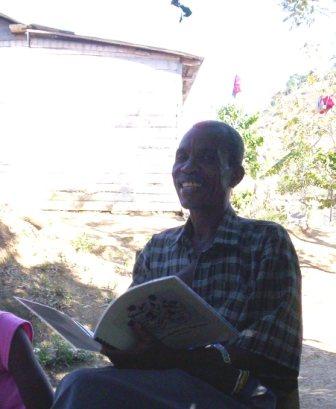

But Saül is very good with money. He’s known among family and friends for his financial smarts. It’s a running joke. The intelligence he shows handling money is all the more striking because that same intelligence did him no good at all when he was a boy in school. After spending several unsuccessful years in third grade, he convinced his parents to let him drop out and go into business instead. It must have been a hard decision for them. One need only consider how far the other siblings have been able to go in school to understand how dedicated the family has been to education. Four of the seven have made it to university, and two others made it to the last few years of high school. This, in a country in which only 60% of the population is literate and less than half of school age children are enrolled in primary school.

One of Saül’s godchildren is a boy named Serafen, who lives in Ench. The boy’s father, Rosemond, is not only Saül’s //monkonpè//, but they are cousins as well. Saül’s father was raised by Rosemond’s grandparents, having been adopted by them when his own mother died in childbirth. His father had died just a few weeks before that. So Saül feels close to Rosemond, and listens to his advice carefully. Rosemond has done very well for himself selling gasoline, ice, and soft drinks in Ench, and he advised Saül to make a go of selling gasoline as well.

This is not to say that Saül was to open a gas station in the sense that we know them. Even Rosemond, who has a large and flourishing gas trade, is a long way from anything like that. Rosemond has a small shop at the side of the road in downtown Ench. It’s filled with barrels of gas, which he empties into gallon jugs to sell. Rosemond was advising Saül to buy a couple of barrels. He gave Saül a connection to someone who sells gasoline wholesale. Saül decided to buy some gas and get to work.

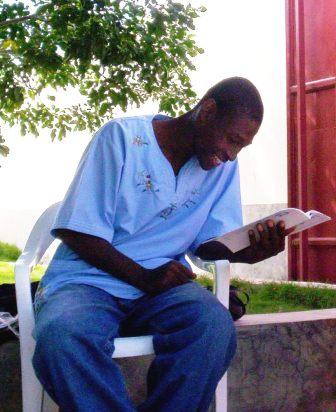

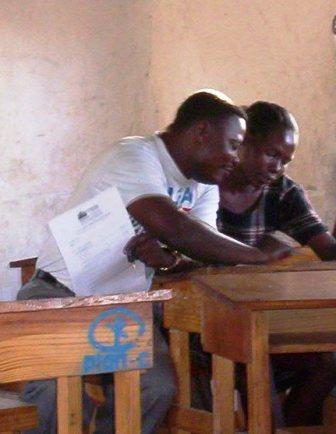

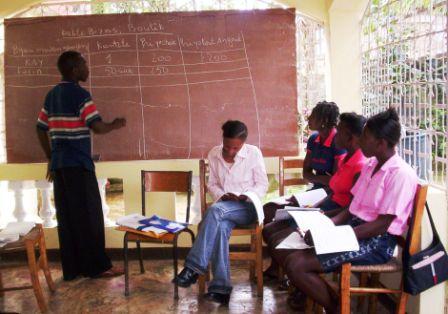

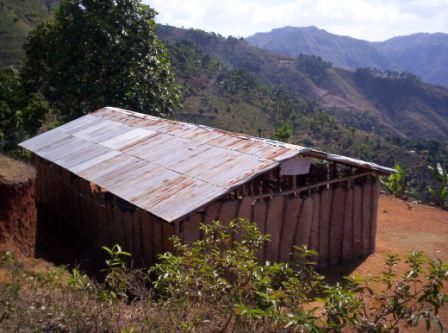

Here’s Saül’s warehouse:

But it’s not that simple. Saül could not afford to simply give up his job to become a gasoline merchant. The steady, if small, salary it provides is important to him, and the housing is more important still. So he hired a young salesman. He paid him a very small salary to sit by the gasoline all day and sell it to passing drivers.

It didn’t work well. The guy was lax, unreliable, too inclined to sell on credit without keeping close track of who owed what. So Saül had to fire him. Saül was thus left at something of a loss. He had a supply of gas, but no consistent way to sell it. He would not be able to move it quickly enough working the streets only in the hours when his job didn’t require him.

Then one day another young man came by looking for Saül. At the time, the young man was running his own small business at the tap-tap station at which Saül had been trying to sell his gas. When one of the drivers asked him where the gas was, he ran to get Saül, and made the sale for him. That young man was Kenòl.

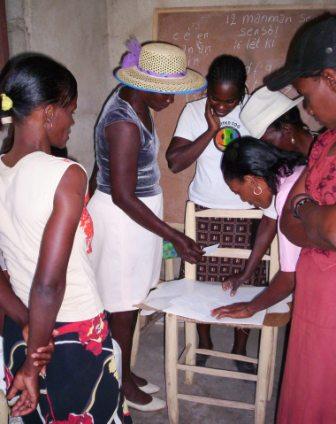

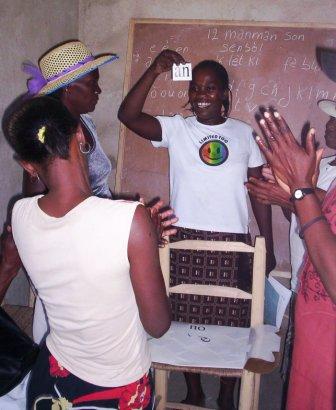

Kenòl is from Okay, Haiti’s most important city in the south. He had been living in Pòtoprens on his own for sometime, putting himself through high school. He had recently made it all the way to the end of high school, but hadn’t been able to pass the national graduation examination. Few Haitians get as far as taking the exam, and very few pass it. I’m not sure how he scraped together tuition to go to high school, but as much as he would have liked to continue his education by enrolling in a professional school, he just didn’t have the money. Rather than sitting around, feeling sorry for himself, he began selling the phone cards that cellular phone users in Haiti need to make calls. Soon after that, he started renting a phone from someone so he could sell telephone calls, too, operating a kind of payphone. Neither of the businesses brings in much income, but by working the streets seven days a week, from sunrise to dark, he was keeping himself fed.

Saül and Kenòl began to talk about how they could run the gas business together. They didn’t know each other very well, so they weren’t sure what to expect. Rather than Saül just paying Kenòl, they decided to try something different. They would become partners. Saül would buy the gas and pay the expenses to transport it to the tap-tap station where Kenòl has his other businesses. Kenòl would sell it. They would split profits 60/40. Saül would get a hardworking, motivated salesman, and Kenòl would get a piece of a business larger than anything he could afford to establish himself.

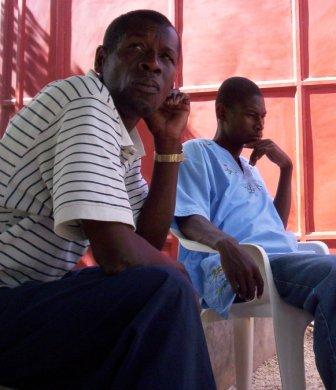

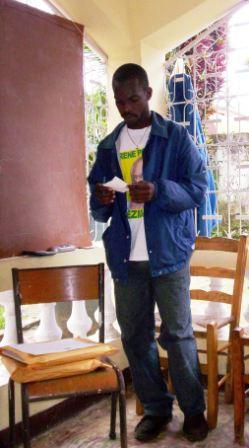

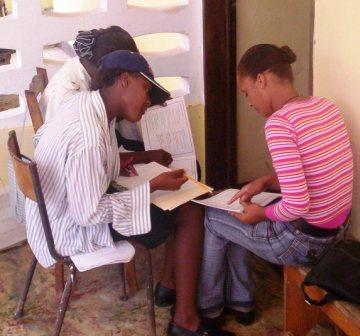

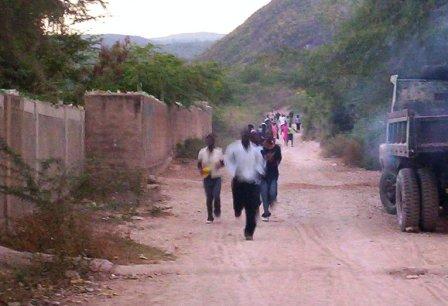

Kenòl at the station:

Here you can see his phone business, too:

The business appears to be going quite well. They sell about a barrel of gas each week, plus smaller quantities of diesel and kerosene on the side. I asked Saül why sales were so good. There are, after all, several modern gas stations with pumps and convenience stores nearby. He explained things in two ways. On one hand, though the gas stations are nearby, he sells right at the station, so tap-taps lose no time filling up. They can buy a couple of gallons while they wait for passengers. This much I had guessed. But he said that what is more important is the fact that they sell the gas in gallon jugs. Drivers like the assurance that they are getting a gallon when they pay for a gallon, and Saül’s system allows them to feel sure. They do not trust gas station pumps.

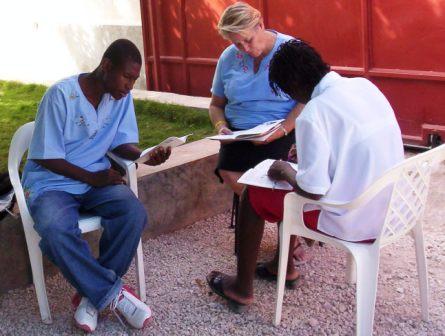

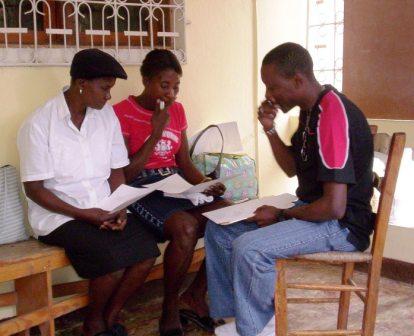

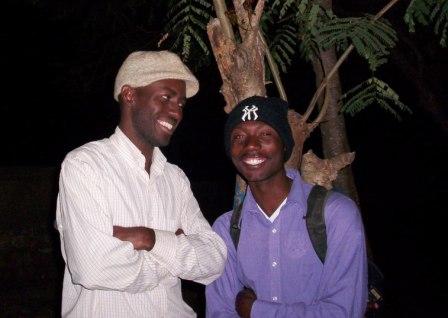

Along with their partnership, a friendship is taking shape as well. They are very different people, from different parts of Haiti, with very different stories to tell. But Saül trusts Kenòl more and more, and likes him for both his seriousness and his wit. He appreciates the casual respect that Kenòl shows him. Kenòl respects Saül’s business acumen and enjoys his easygoing ways. While Jidit and the boys are in the countryside, Kenòl and his girlfriend, Rosena, have been Saül’s main companions. They’ve been eating together two-three times every day. They both celebrated birthdays in July, and made a point of celebrating them both together.

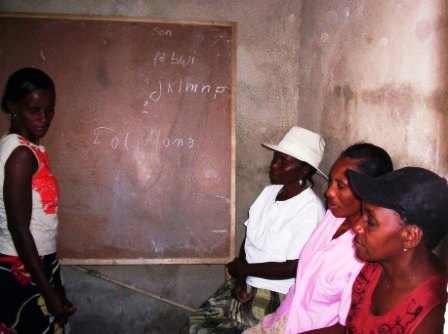

One thing that they have in common is that, though there is no comparison between their respective educations – Saül is only marginally literate, while Kenòl reads both Creole and French with ease – as bright as they both are and as hard as they both work, neither was able to make formal education a road to a better life. This they have in common with far too many Haitians. For the majority, the primary barrier is economic, as it was for Kenòl. But for many, like Saül, it is the quality of the school experience itself: the rote learning, the primacy of French, the violent and overcrowded classrooms, the poor teaching.

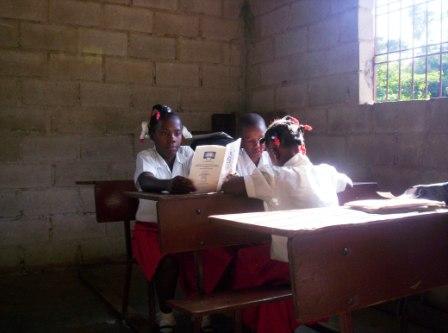

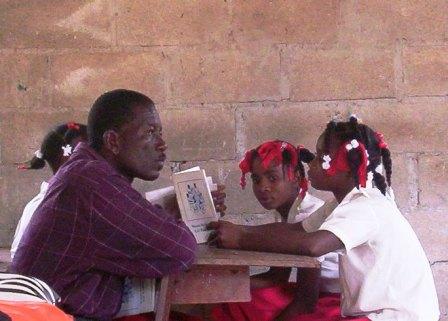

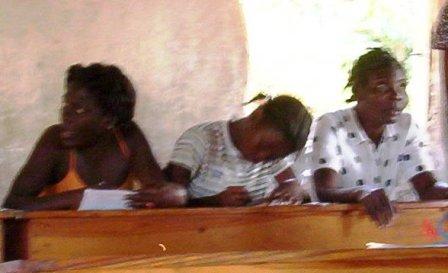

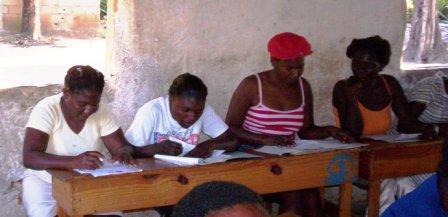

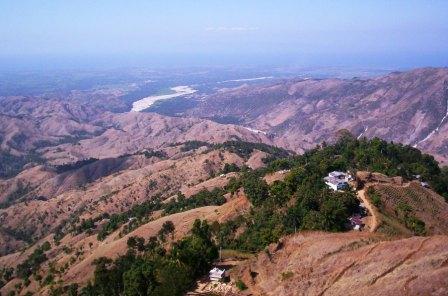

It leaves one pleased to know that there’s such a place as the school in Matenwa (See: www.matenwa.org or EducationInMatenwa), and relieved to see that at least some people are finding ways to make their living nonetheless.

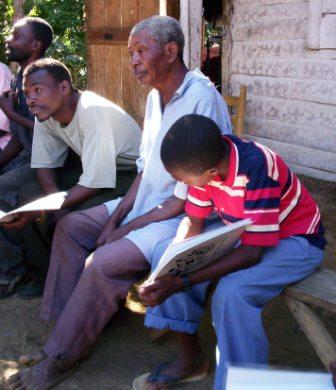

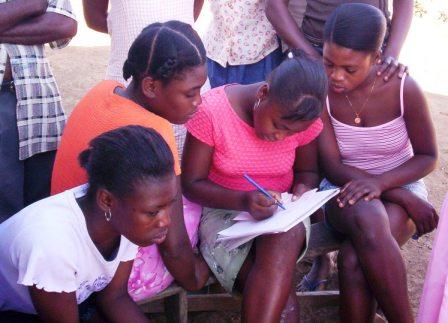

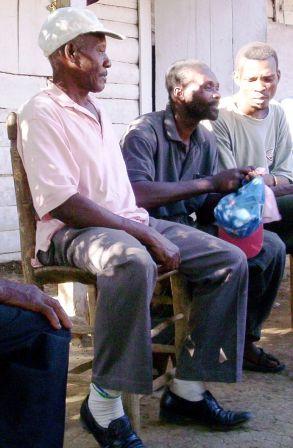

Here they are on the evening of Saül’s birthday dinner. That’s Rosena, Kenòl’s girlfriend, on Saül’s left.