Once again, a year has passed. It’s time for me to write another summary of my activities in Haiti. I’ve now been living and working here in Haiti for almost three years. I make an effort to keep my friends outside of Haiti informed about my work through the photos and essays that I post on the site. I hope they are interesting. I know that I’ve slowed down some. They’ve gotten a good deal less frequent. But writing them continues to been an important source of learning for me and of encouragement when, as occasionally happens, a reader responds with questions of comments.

Once again, I am dividing the report by partner. I hope that reading it is useful. Please e-mail me with any questions at [email protected].

Fonkoze

My most substantial collaboration continues to be with Fonkoze, Haiti’s largest and most successful micro finance institution. Fonkoze provides small loans to poor, mainly rural Haitian businesswomen. It is a very dynamic institution. Having grown from 29 to 32 branches so far this year, it will have 34 by year’s end. As many as eight additional branches may open in 2008. Its reach extends to nearly every part of Haiti, with roughly 50,000 micro credit borrowers and a realistic vision to serve over 200,000 by 2011.

From its beginning, Fonkoze has known that as important as access to credit can be in the fight against poverty, it is not enough. Fonkoze supplements its lending with educational programs like Basic Literacy, Business Development Skills, and Reproductive Health Education. The programs are provided to Fonkoze’s members free of charge. For women living in poverty, the struggle to provide for their families and to pay back their loans with interest is hard enough. Asking them to pay for educational programs, as important as these might be, would be unrealistic.

The programs are inexpensive. It costs about $25 to offer a participant a four-month class. But the scale of the institution means that they require a lot of money nonetheless. Full implementation of educational programs all Fonkoze branches would have cost about $2.4 million in 2007.

My involvement with Fonkoze started small: I was to work with a team of its literacy experts to develop a complete set of lesson plans for the Basic Literacy curriculum. It soon spread from coordinating the implementation and reporting for a large grant covering programs in three branches, to grant-writing and reporting on all of Fonkoze’s educational programs, to hiring of staff. I also have translated for Fonkoze visitors and conducted client interviews for publication. Fonkoze calls me its Director of Education.

We’ve met with some success. By late in 2005, Fonkoze had educational programs operating in only six of its branches. Thanks to aggressive pursuit of grants and other monies, we’ve had programs in 23 branches in 2007. My grant writing duties have extended beyond just the literacy programs. In all, I’ve had a hand in raising about $1.8 million for Fonkoze, with more on the way.

Last year, I wrote that I was encouraging Fonkoze to hire a full-time director for its educational programs. The program had outgrown what I could keep up with. It did so shortly after I wrote my summary. Though Myriam Narcisse is not fulltime, she is a first rate administrator, and is providing the program with the leadership it needs. Hiring her has freed me to concentrate more on writing and on working with Fonkoze’s field staff.

And working closely with field staff remains important. Though we have taken a range of measures to push the programs more towards dialogue, the shift is challenging for a staff which itself has little experience of education through conversation.

One step that has proven enormously helpful in this respect has been the hiring of Emmanuel Blaise, an educator who has a strong background in dialogue through his long participation in Wonn Refleksyon, of Reflection Circles, the method based on the Touchstones Discussion Project that I helped establish with the Beyond Borers team that originally invited me to Haiti. Manno is in the field almost fulltime, working with Fonkoze staff.

In addition, as its need for a steady stream of new employees has increased, Fonkoze has become aware of problems in the way it trains them. I have been participating in its attempt to address this problem in two ways.

First, over the past year, I have become increasingly involved in working with both new and experienced field staff from outside its education department. I’ve been focusing especially on loan officers, the staff member with the most important face-to-face relationship with member/clients. Fonkoze’s method of making loans requires, among other things, that these officers be capable of leading meetings at which their borrowers do most of the talking. In a larger sense, they need to be good listeners. And I’ve been creating lesson plans that help them lead discussions and been working with them individually and at large workshops as they learn to use these plans. (See: Security in Foche, What Conversations are About, More about Texts.)

Second, I assisted in conceiving a new kind of branch to be opened in Lenbe, in northern Haiti. I also helped secure several hundred thousand dollars of funding to make the branch possible. The Lenbe branch will be a master branch. We’re calling it an “Active Learning Center.” It will be a locus of Fonkoze’s efforts to improve its work in two senses. On one hand, it will have an advanced capacity for field research and analysis, with two staff members dedicated to better understanding issues like how Fonkoze’s programs affect its clients and what opportunities there are for those clients within the economy they live in. On the other, it will be staffed by experienced and strong-performing employees from across the Fonkoze system. They will be charged with the responsibility to serve as guides for apprentices who come to the branch for short-term stays.

I am now working with Fonkoze leadership to open the branch and to learn how to use the opportunities it will afford. I expect this work to be a major part of my activities in the coming year.

I also want to help Fonkoze find more English-speaking staff to help with the grant writing and the communication with donors that takes up a good deal of my time, time that I could usefully spend in other ways. It is my view that Liberal Arts types, with strong writing and analytical skills, could be very useful here, and I want to help Fonkoze figure out how to attract such help.

Matènwa Community Learning Center

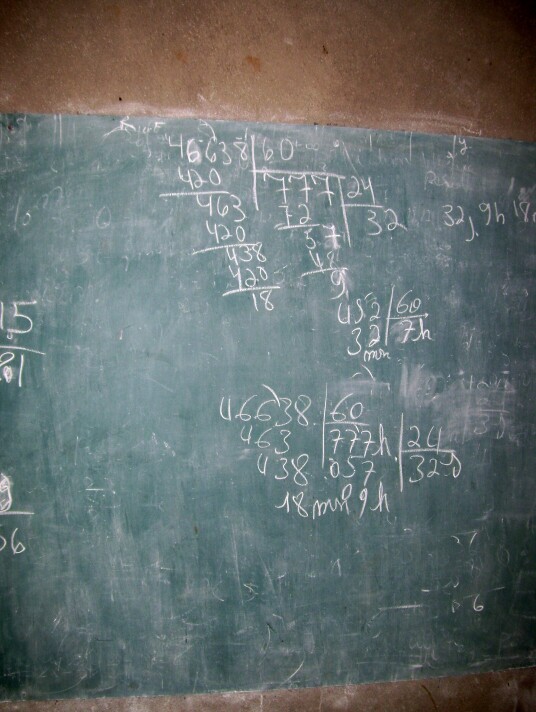

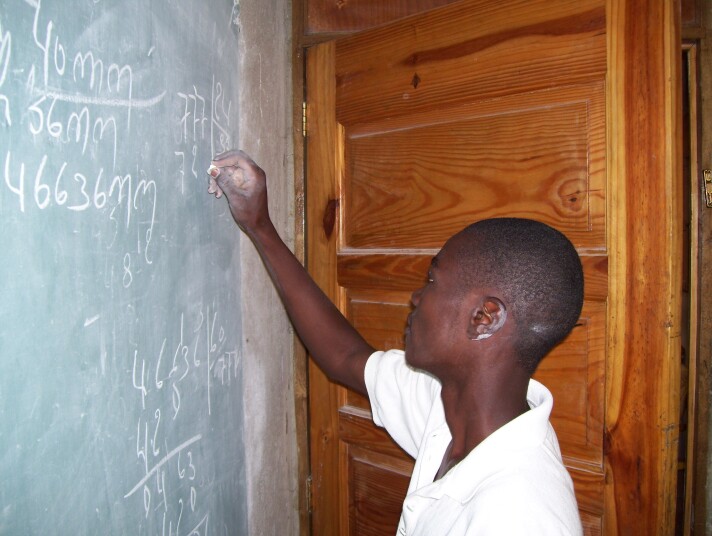

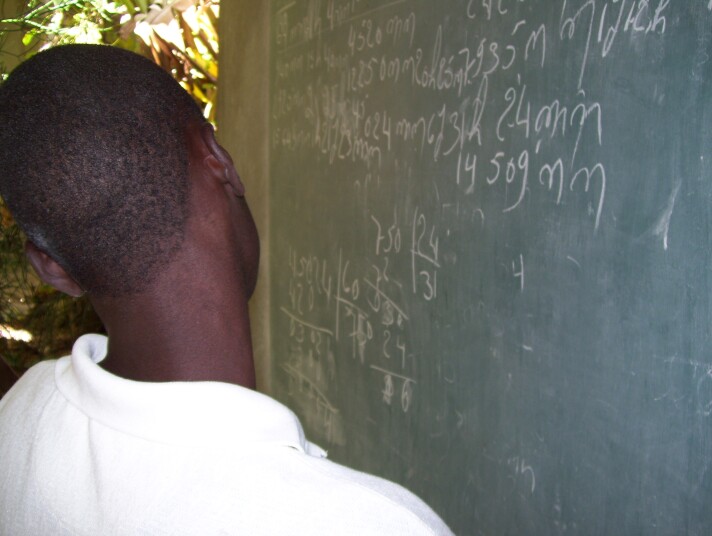

My longest running collaboration has been with the school in Matènwa. We’ve regularly undertaken little projects together – books, articles, or techniques we decided to study – even during the years I was based in Waukegan. For example, we once spent a few days reading a French version of an ancient geometry text by Euclid. We wanted to see whether participating in conversations about definitions and proofs could help them to see more openness in mathematics and to discover ways to open up their own teaching of math.

It’s not easy to summarize what we have done together. Much of our work amounts mainly to a little bit of this, a little bit of that: small classroom experiments like one I undertook in map making with the fifth grade teacher, Enel Angervil, and his students. (See: Mapping Our World.) I helped the sixth graders occasionally with math as they were preparing for the national primary school graduation exam and even served as their substitute teacher for a day. (See: Kou Siplimantèa.) I also led a two-day seminar on using microscopes in the classroom.

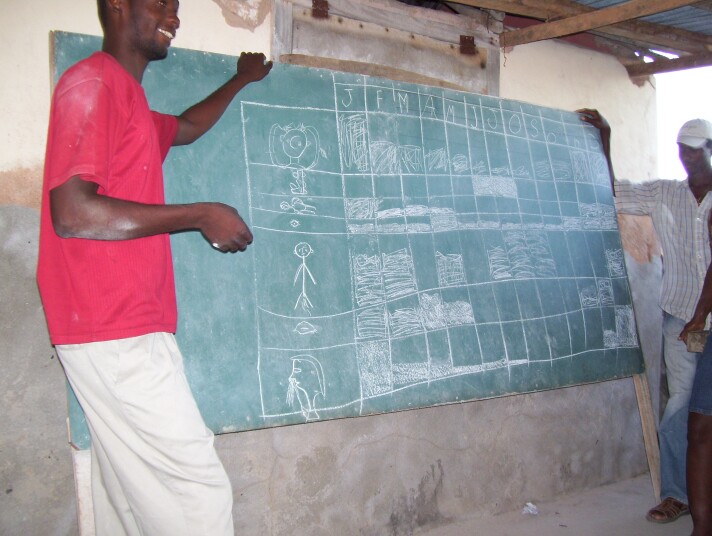

But there were two larger initiatives we undertook together as well. One was a first experiment with a literacy method called “REFLECT”, the other was a workshop we designed led together on the psychology of learning for teaches for other Lagonav schools. I’ve written about both. (See: Learning to REFLECT and Lekol Nomal Matenwa.)

The REFLECT center had mixed results. We learned a lot, but we can’t say we were really pleased with the degree to which we were able to engage participants or the progress they made. One conclusion that suggested itself was that Matènwa, where the center was located, has had enough literacy work over the years that the participants we were left to serve were already the hardest to help. Another was that, those who did come to the center had seen enough literacy work in their area over the years that they had already developed fixed ideas as to how those centers should function. They wanted books very focused on letters and syllables, whereas REFLECT was asking them to focus on community development and thinking about their own lives.

So we decided to attempt a second experience with REFLECT this year in another part of Lagonav. It was an easy decision to make, because we had colleagues from Pointe des Lataniers, a small village on the western tip of the island, who were anxious to find some way of combining literacy work with the work of facing the community’s very substantial problems.

Initial results are exciting. If nothing else, the community is participating, and they are starting to face the problems that REFLECT helps them identify. One problem we had in Matènwa was that the number of consistent participants was low. We had dropouts throughout the year. In Lataniers, we started with about 15 participants, but that number has doubled in the weeks following the center’s opening as community members began seeing what was going on in the center. In addition, participants are already making clear progress. They’ve hauled rocks to raise an area of the community where persistent flooding has left lots of standing water, they’ve undertaken a thorough study of the numbers of children in the area who are not in school, and they’ve identified sanitation and standing water as the issues they most need to address.

We will have problems. Lataniers is a nuisance to get to, so it’s hard to provide the center’s leader, Robert Sterlin, with much technical support. Even telephone communication requires that he travel to the next town. But I think there’s reason for optimism.

We are now in the process of following up the summer psychology workshop. This has two aspects. The most direct follow-up was a decision by the participants in that workshop to create a standing committee to plan further faculty development meetings for Lagonav teachers. The committee has monthly meetings. When I visit next week, I should be able to gain a good sense of the progress they’ve made. I’ve also begun to help the staff think more about its role as providers of faculty development for other schools. The school has a growing reputation, and so has groups of teachers who spend days or even weeks observing and practicing its methods. (See: Where Education Happens.) I’ve been asked to help the school develop both a clear program and an approach to evaluating these interns that will be useful to the institutions that send them and consistent with the school’s core values.

IDEAL

Last October, I began working with a new group, young men from Belekou, a neighborhood in Cité Soleil, Haiti’s most notorious slum. (See: Meeting a New Group.) It has quickly become the most intense involvement I have, even if it remains something I squeeze into my spare time.

The involvement has been intense because of the level of need that the guys initially showed. I had never really met with a group that hadn’t already been organized to some degree, whether as a classroom of students, a school’s faculty, or an organization’s members or its staff. The guys in Belekou didn’t really see themselves as anything, except as young men who wanted to make progress without entering into the logic of gang membership.

The first thing the group asked for was English classes, and as hard I it was for me to imagine their usefulness, I felt bound to follow their lead. (See: Progress Without Direction.) Another of their first priorities was to get organized. This they understood to mean establishing their organizational identity on paper. By inviting an old friend, Gerald Lumarque, to work with them for two days, I was able to help them accomplish that goal. (See: IDEAL.)

But those were the easiest kind of goals to accomplish. More meaningful goals, like helping them find ways to work together to change their lives for the better have naturally been more elusive. Even so, I think we’re making progress of this front.

They were able, with my help, to secure a loan to open a small bakery. And though the bakery isn’t yet functioning very well, it is functioning. They are making their scheduled repayments, though not quite on schedule, and regularly improving the way they function in terms of transparency, fair division of labor.

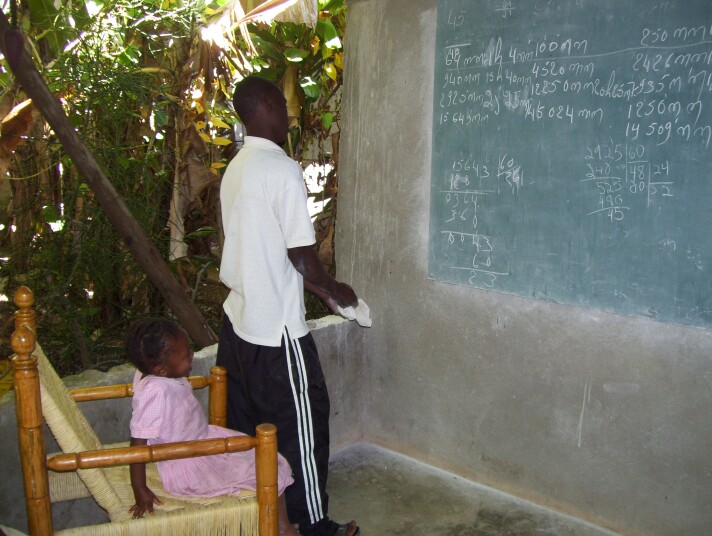

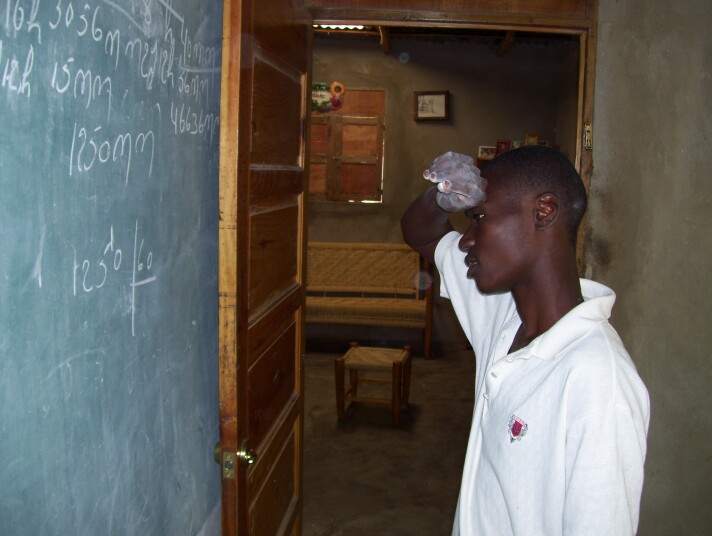

They have recently begun to focus on a newer, more ambitious goal. They’d like to open a school for kids in their neighborhood that haven’t had the chance to attend. This will require stretching themselves. They’ll need to stretch their imagination to think about what a school can be without all the resources that even the poorer schools they are familiar with depend on. And they’ll need to stretch themselves as they figure out how to do the various parts of the job that they’ll need to do, like teaching, administrating, and dealing with parents.

Working with them to build a business and a school will be a challenge. The guys are not the only ones who’ll have to stretch themselves. But both initiatives should be able to exemplify what learning together with my collaborators can mean.

Conclusion

These are just the largest involvements that I have had and expect to have. One of the beauties of my increasing time here is that I come across more people and more groups who are interested in working together. There are groups from the States, who seek help with translation or other aspects of visiting Haiti, and groups in Haiti, who look for ways to strengthen education programs they run or want to run.

As I wrote last year, there continues to be plenty to do here in Haiti. Shimer College last spring agreed to extend my assignment here in Haiti through this current academic year. There is, in other words, no reason for me to think of returning before September 2008.