Ti Kèl and Mackenson are the best of friends. They are sixteen-year-olds, who sit next to each other on the same bench of the 5th grade class at the public school in Mariaman, where my neighbor Mèt Anténor is principal. They both come large families. Ti Kèl’s mother has ten children, and Mackenson is one of seven.

They are both unusual in their families, but not unique, in their deciding to try to take school seriously. One of Ti Kèl’s five older siblings, a guy named Titi, is well into high school and working hard. If the three kids between Ti Kèl and Titi are not in school, it is nonetheless Titi that he’s chosen as his model. He has been strongly encouraged to work hard in school by his godfather and first cousin, Mèt Anténor, and his parents are both supportive. Mackenson has an older sister living in Pètyonvil who’s in high school, but most of his other siblings are not. He himself decided that he would go to school. His parents are pleased, and they give him the little help they can, but they had no hand in the decision.

This year, they decided to plant a joint vegetable garden. Mackenson’s father, Leon, had some land he wasn’t using that he let the boys borrow, and the planted tomatoes, sweet peppers, and corn back when the rains started in late February. It looks as though there may be a decent harvest. There’s been an unusually good mixture of sunshine and rain.

They asked me to take some pictures of the garden to take with me to Matènwa. Ti Kèl has made friends at the school there. Since he heard about their efforts to plant trees, he’s been sending seeds and saplings. He visited last summer, and made many fast friends.

They are especially pleased with their tomatoes, which are really loaded.

One of their two plots of corn is growing well too. The other is in distinctly poorer soil, so it’s struggling. But here’s the good corn:

Their peppers are flourishing.

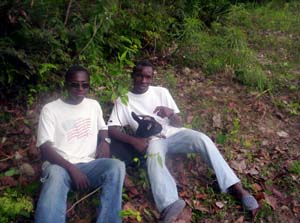

Mackenson’s also raising a goat.

The papaya tree in front of his house is really filled.

They will send their harvest for sale to Pètyonvil. Their mothers will probably do the actual selling. But the should make some money.