I don’t know how long Gislène and Léon have been together. Suffice it to say that they’ve been together a long time, long enough to have twelve children. And though only nine of those children survived infancy, the oldest ones are married and in their thirties and the youngest is Nadine, a fourth-grade girl in her early teens.

They were not, however, ever married. Not, at least until Sunday. Early last week, I went by to see how Léon was doing, and as I was leaving he asked me to come to his wedding. Léon hasn’t been well. He has had kidney trouble. He’s been weak and in some pain. My doctor came up to see him and arranged several tests for him down in Port au Prince.

I hadn’t heard about the wedding. But, then, neither had most of the rest of our small community. They had chosen, for whatever reason to keep things quiet. When I mentioned it to Madan Anténor, with whom I do most of the gossiping that I do in Haiti, she was delighted, but also very surprised.

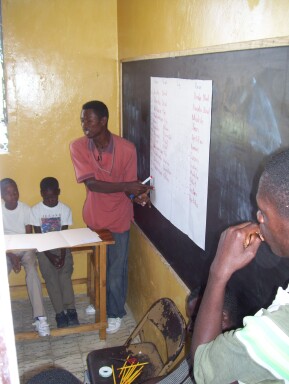

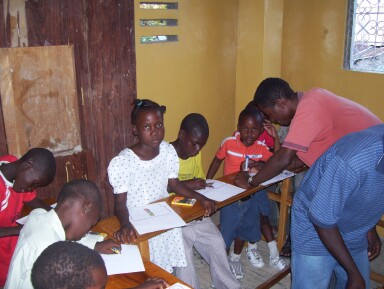

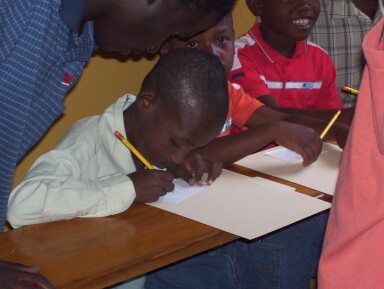

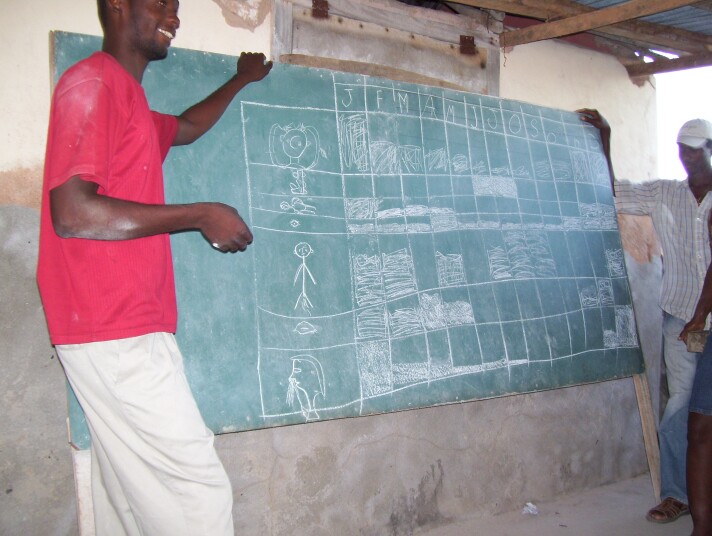

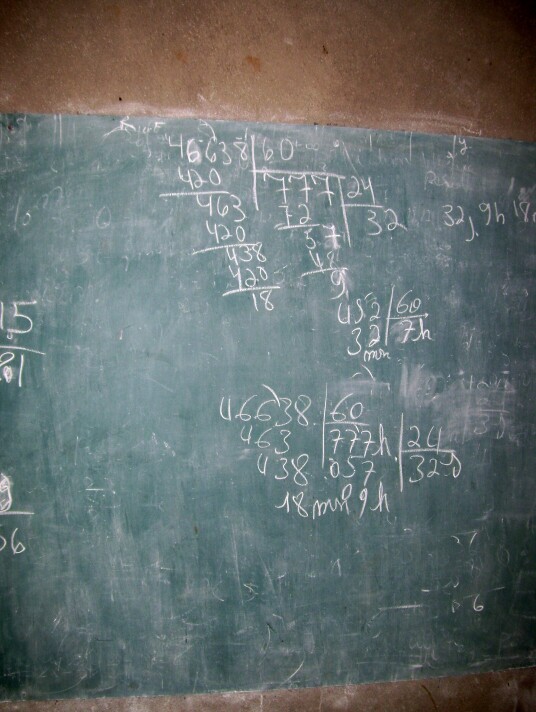

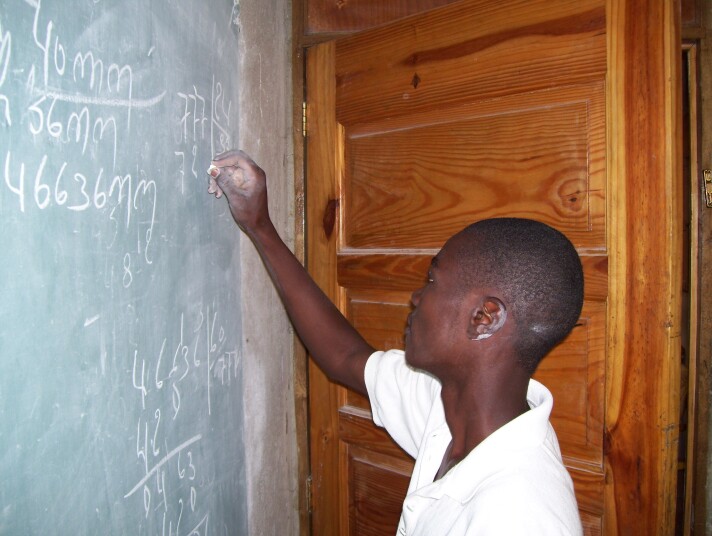

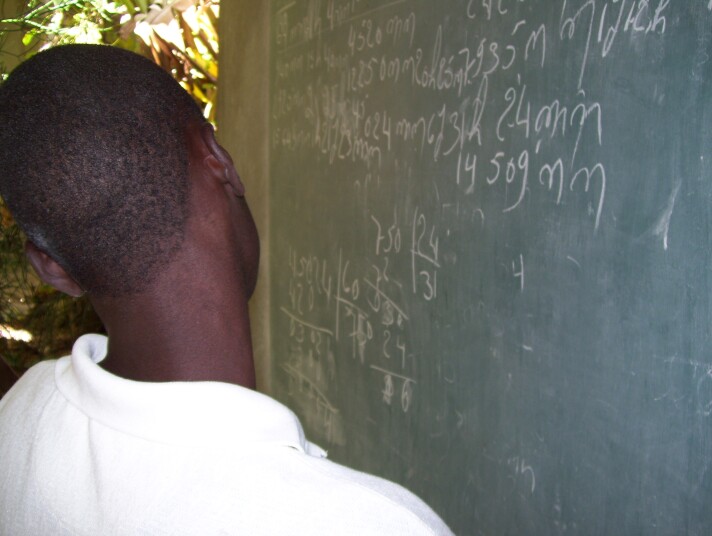

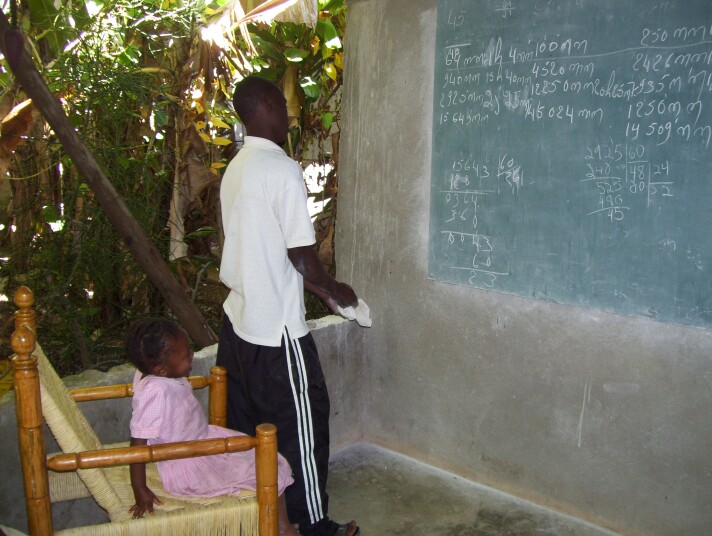

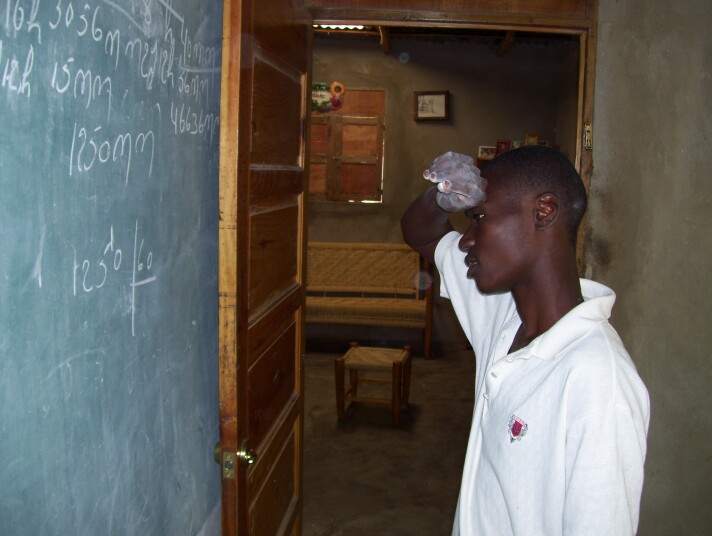

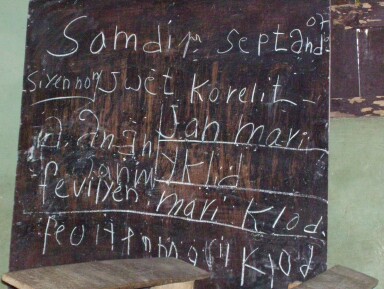

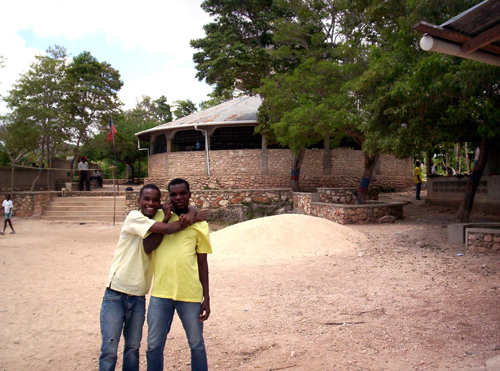

I went to the church with Mackenson, their third-to-last surviving child and the member of their family I know best. He has been doing math with me on the blackboard I put on my front porch for a couple of years. He also does odd chores for me when I need someone. He’s an eighteen-year-old, now finishing the sixth grade. He’s especially attached to his dad, and he couldn’t have appeared happier.

He was the only one of the children who went to the church, and he and I arrived late. I wasn’t the only one wondering whether his lateness and the other children’s absence from church was a sign that they didn’t really approve of the proceeding. An older woman came up to him after the ceremony and asked him about that directly. He answered that they were all happy about the marriage, but that the others were organizing the reception.

The church they held the wedding in is really just a palm-leaf enclosure in someone’s backyard. The ceremony was held on the occasion of a visit by a pastor from down in Port au Prince. He doesn’t come often, but he’s the one in their congregation with the legal right to marry couples. The place was decorated with white sheets, which were used to cover the deteriorating palm-leaf walls. There were balloons scattered here and there that gave the space some artificial color.

After the service, the first challenge was to get back to the road, where a car was waiting to take them to the reception. It was a hard little walk for Gislène, who was wearing very high heels with her long wedding gown.

The reception was held at Gislène’s small, one-room house in Ba Osya. That’s the next village up the hill from Ka Glo. Gislène and Léon do not live together, and they don’t intend to any time soon. She lives with their youngest daughter, and he lives with their two youngest sons. I’ve been told that the separation has nothing to do with conflict between them, that it is, in fact, a simple but effective form of birth control that they agreed to when their twelfth child was born and then died.

Most of us got to Ba Osya on foot. It’s not far. But it’s traditional for Haitian couples to get a ride to the reception. Normally, this would mean on horseback. But Léon and his family have long been connected to the family of one of my neighbor’s Madan Boby, and her son has a small vehicle. He seems to have learned neighborliness from his mother. He gave them a ride. But then they waited for me to get there so I could photograph the arrival.

There was a small crowd waiting, and it included most of their children, children’s spouses, and grandchildren. Any question of their children’s feelings about the marriage was quickly put to rest. They were in very high spirits: cooking, serving, entertaining, and serving as the parents’ hosts in their own mother’s house.

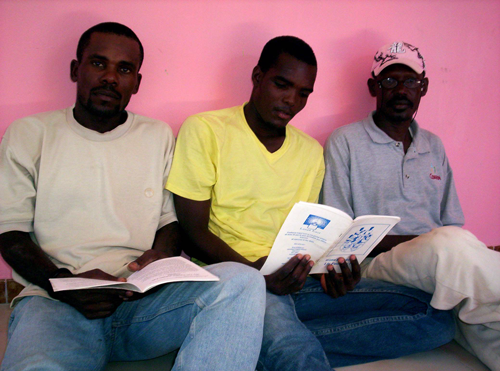

Shortly after I sat down with other guests under a tree, Mackenson called me aside. He invited me into the house to have a bite to eat. One of the challenges of hosting a Haitian wedding reception is that you don’t know how many people will attend, and every one who attends expects to be fed. It calls for a mixture of kill and diplomacy. I was invited to join the most important guests, who were eating first inside the house. Feeding us inside meant that the hosts could conceal from others just what they were giving us. We were offered the more expensive dishes – meat, salads, and fries – which were in short supply. Other guests would get beans and rice.

I don’t know Léon really well, and I hardly know Gislène at all, but I know several of their kids, and they are really nice people. They speak well for the folks who raised them. I wish them years of happiness together.